Set Description

For those unfamiliar, the title is part of the lyrics from the Broadway hit " Hamilton". The lines are sung by King George III in a song to the American people after they won their independence from England. Although I have never been a big fan of musicals, I love how Lin Manuel Miranda combined artistic talent with history in such an approachable modern way. I am not alone in this thinking; in fact, the play has inspired countless people and continues to reach international acclaim. During an anniversary trip to Europe, my wife and I had the privilege of seeing this play in London. I walked out of the theatre thoroughly impressed and with the lyrics, which by this point were already memorized before the show, playing on repeat in my head. The following day was my birthday, and my wife had promised a day full of antiquing and coin shopping. We started with a few antique stores and eventually ended up at Baldwin's, where I purchased an 1807 proof restrike halfpenny for my growing George III copper collection. It suddenly hit me. I could detail my numismatic adventure while also telling the history of English copper under the reign of George III. To make it even better, the lyrics from Hamilton could play a role!

Engraving provided by my friend C. C. of Crystal River Florida Engraving provided by my friend C. C. of Crystal River FloridaThe first part, "What comes next?" could help set the stage for how under George III's reign, the English people were finally provided with something that had been absent in commerce for centuries: a sufficient supply of high-quality regal copper coinage. As readers will soon discover, small change was scarce, and lightweight counterfeits and tokens made up the bulk of currency exchanging hands among the poor working class. The question of "What comes next" was asked by many over several centuries in an attempt to find a solution to the small change crisis throughout much of Europe. The second part, "You've been freed", could subsequently be interpreted as the English people's newfound freedom from rampant counterfeiting, which plagued the copper coinage produced by the Royal Mint for centuries.

The third part of the title, "Do you know how hard it is to lead?" could speak to the lasting impact of the Soho Mint and how Matthew Boulton's work revolutionized the minting process. In part, this set aims to walk readers through the history of the Soho Mint and how the ingenuity of Matthew Boulton ultimately addressed the question of "What comes next?" not only for English coins but also for coins that would circulate the world. With the application of steam-powered engines to minting, a new unprecedented quality and quantity of production were made possible. In my humble opinion, the Soho Mint products are some of the most exciting pieces that portray a story of rapid advancements in the art and science of minting. This era of profound development played a critical role in curbing mass counterfeiting and established a legacy that can still be felt some two centuries later in our modern coinage.

Studying the seemingly endless array of products of the Soho Mint is no easy task, and as readers who choose to embark on this journey with me will soon learn, a lot is left to be discovered. The main description aims to provide a historical backdrop to the era in which the pieces in this collection were produced. The detailed pictures and brief descriptions that accompany each piece in this set provide readers with a source of pertinent information unique to that specimen. This will likely be a pursuit of mine for years to come, and I have no illusion that it will ever be perfect, but I hope that those of you who choose to follow along enjoy the journey.

Introduction:

The Soho Mint's backstory and its owner, Matthew Boulton, tells a fascinating story of national pride, ambition, and perseverance. I hope that this write-up can afford you a glimpse into the history of the Soho Mint, the struggles it overcame, and the undeniable legacy it amounted to. To keep this write-up from becoming too long, I have opted to forgo any biographical details of Matthew Boulton and instead focus on the relevant information about the mint. For those you interested in learning more about Matthew Boulton or James Watt, I point your attention to the "recommended readings" section at the end. Here you will find a handpicked selection of relevant literature.

Soho's calling:

Like most parts of English history, the struggle surrounding small denomination currency is long and somewhat complicated. According to Brooke (1932), the lack of small change in England can be traced back to the 14th century but remained unresolved until the 18th century. Throughout the earlier portion of this five-hundred-year span, tiny silver pieces were used as pennies and halfpennies, but when silver prices started to rise, the already dwindled supply became nearly non-existent. This marks an exciting era for English numismatics. James I and Charles I sanctioned the production of copper tokens, but as noted by Peck (1964), these were not regal copper issues. There was no mandate requiring their acceptance within the general public, and they were only valid among those willing to accept them. According to Brooke (1932), the relentless demand for lower denomination currency allowed the token coinage to prosper. He notes that token coinage made the majority of lower denomination currency in England, which seems to peak in the late 1640s until Charles II issued regal copper coinage in 1672. To clarify, not all of these tokens freely circulating were sanctioned by the crown. In fact, a large portion of them were illegal, but the practice was not suppressed, and as such, the problem ran rampant.

In response to the growing issue of lightweight and illegal token coinage, Charles II issued the first run of regal copper coinage. The mint was woefully unprepared to produce enough copper coinage to suffice the demand, exasperating another issue that would plague English copper for several more centuries- counterfeiting. As noted in a 1672 issue of the London Gazette, Charles II reinterested that the practice of counterfeiting was illegal. This did little to curb the issue as the offense was only classified as a misdemeanor with minimal punishment. Counterfeiters could make a handsome profit by melting down regal copper issues and using the material to produce lightweight fakes. The counterfeiting issue became even more extensive when Charles II, like many of his successors, decided to strike coinage in tin. According to Brooke (1932), the material was readily available and offered a much larger profit margin than their copper contemporaries. Eventually, tin was abandoned altogether under William III; however, counterfeiting of the copper coinage persisted. The contractors' poor craftsmanship further compounded this as many "genuine regal issues" were underweight and struck on cast blanks. To make matters worse, there was a complete lack of proper distribution, which resulted in a glut of copper in cities like London but did little to address the country's needs as a whole.

Similar issues persisted throughout the reigns of Anne and George I and had reached a head during the reign of George II. By the end of the 1730s, counterfeiting had become such a widespread issue that he little choice but to restructure the anti-counterfeiting laws haphazardly issued by his predecessors. According to Peck (1964), a new law was enacted in 1742 to escalate the punishments for counterfeiting offenders and changed how these charges were pursued. The new law allowed convicted offenders to receive a lighter sentence if they provided information that led to further arrests. If the information and testimony led to at least two others' convictions, the charges were dropped. The new law also allowed investigators to offer a £10 reward to non-offenders who offered information that led to additional arrests. All good intentions aside, the new law fell short due to a profound legal loophole. Peck (1964) notes the law did not explicitly make it illegal to produce copper pieces with noticeable differences from their regal counterparts. For instance, they were producing "coins" with a misspelled legend, incorrect date, incorrect ruler, or maybe even a famous person in place of a monarch. The prosecution of these individuals was rendered nearly impossible, and the trade of making these "coins" took off. As noted by Peck (1964) and Brooke (1932), these operations had advanced to multifaceted businesses. They also used more sophisticated techniques, such as a hand-operated press. These criminals were savvy and created an entire underground counterfeiting operation with multiple parties involved. The capital of which was in Birmingham, and this was no secret. In fact, a mint official visited the town in 1744 to investigate, which led to several convictions (Peck, 1964). The town's reputation was so bad that it became known as "Brummagem" (Selgin, 2011).

COUNTERFEIT 1775 1/2 PENNY |

The beginning of George III's reign repeated many of the same errors of his processors. The large unwashed masses urged for more copper coinage, the request was ignored, and counterfeiting ran rampant. Eventually, George III did authorize the production of regal farthings in 1762 and 1763, all of which were dated 1754 and had the bust of George II. The production was insufficient for the demand, partially because the Royal Mint was still using hand-operated presses to produce coinage (Peck, 1964; Doty, 1998; Selgin, 2011). This was a time-consuming, expensive, and at times dangerous task. This physically demanding process required no less than three workers to operate at any level of efficiency. Given these circumstances, it is not surprising that production was so limited. The mint also made less profit on the copper than gold and silver coinage, which undoubtedly factored into their disdain for producing the lower denomination currency.

Despite the lack of desire on behalf of the Royal Mint to produce the copper coinage, the demand continued to grow until it came to a boiling point. The industrial revolution was in full stride during the decades between 1750 and 1775. The industrial revolution led to the large scale adoption of a wage-based compensation structure for workers (Peck, 1964; Selgin, 2011). These workers did not earn enough to be paid in silver, much less gold. They needed lower denomination copper coinage. This demand was primarily met with heavily degraded regal copper and countless lightweight counterfeits. The counterfeiting issue that had already plagued England for centuries had now evolved into a fully operational business that generated a handsome profit for the criminals (Brooke, 1932; Peck, 1964; Selgin, 2011). The issue was so extensive that some estimated that nearly 98% of the copper coins circulating in England at the time were counterfeits (Doty, 1998; Selgin, 2011). According to Peck (1964), a 1798 Royal Mint report estimated that only 8% of the circulating copper coinage resembled the regal copper produced at the Royal Mint. A new law was enacted on June 24th, 1771, making counterfeiting of regal copper a felony, but it had little effect. So, for now, employers and workers would have no choice but to freely circulate inferior "coinage" worth substantially less than its intended denomination.

The centuries of inaction by the monarch, extensive counterfeiting, and the pressures of the industrial revolution all collaborated to create an environment ripe with opportunity for change that Boulton took upon himself to pursue. This backstory may seem tedious, but it is essential first to establish the historical context with which the Soho Mint came into existence. Without it, one cannot fully appreciate the significance of the Soho Mint.

Soho's formative years:

Matthew Boulton and his business partner James Watt were not immune to the lightweight counterfeits freely circulating. The two had several operations that required the employment of many workers, all of which were paid wages that demanded smaller denomination coinage. To this extent, they were forced by no other option to circulate these lightweight counterfeits, making it clear why Boulton might be motivated to build the Soho Mint. What may be less obvious is how Boulton's national pride, ambition, and moral conscience may have played into the decision to create the Soho Mint. According to his account, he was not motivated to produce copper coinage for his profit. Instead, he wanted to prevent his workers, and the poor working class more broadly, from being cheated by the lightweight counterfeits that they were paid (Kalra, 2013). His efforts could benefit his workers, but perhaps if he were successful, his ambition would also benefit the poor working-class nationally.

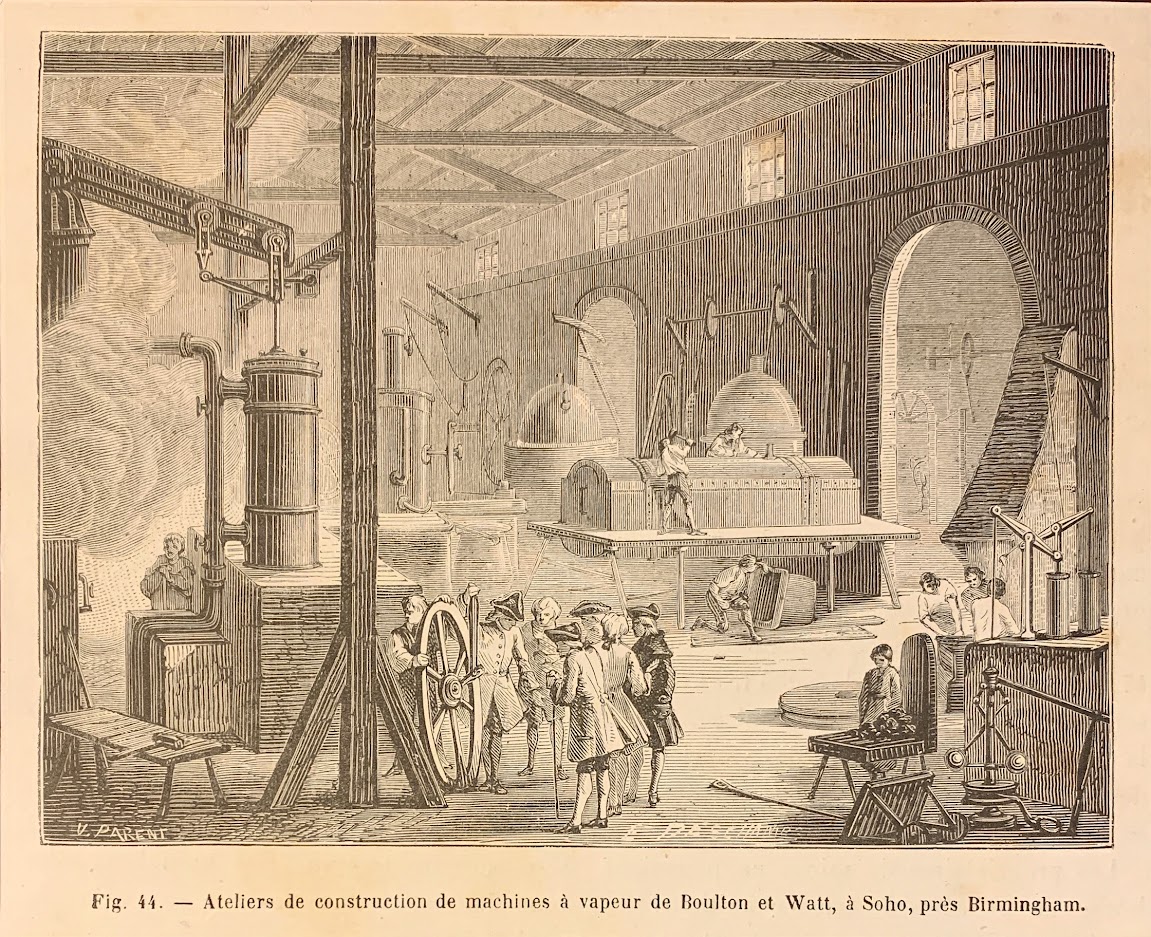

BOULTON AND WATT STEAM ENGINE WORKSHOPS IN SOHO |

Birmingham, the Soho Foundry's location, was the center of the largest counterfeiting ring in England (Selgin, 2011; Peck, 1964). Boulton served on the committee tasked with hedging against crime in Birmingham, so he had a front-row seat of the plight these criminals both perpetrated and suffered (Doty, 1998; Gale & Hist, 1966). The entire town was seemingly laden with criminals whose primary offense was counterfeiting. Still, to some extent, their actions were necessary to ensure the working class could be paid and thus survive. This double-edged sword likely presented several moral conflicts for Boulton. Of course, there is no need to take my word for it. Thanks to the work of Tungate (2010), we have a transcript of a letter he wrote to Sir Joseph Banks in 1789. In this letter, he states, " I took up the subject because I thought it would be a publick good, and because Mr. Pitt had express'd a wish to me of seeing something done to put an end to the counterfeiting of copper coin". All things considered, Boulton's decision to pursue the production of English regal copper coinage at significant personal risk was rather patriotic.

So far, Boulton has been presented in a rather complementary manner. In part, this is because I consider him one of my numismatic heroes, but I would be misguided if I did not mention a few other motives for his involvement with the reform of English copper coinage. The largest of which was his heavy involvement in the copper mining business. At the time, the Cornwall mines were the foremost producers of domestic copper, and their operations required the use of Watt's engines to pump water from the deep mines (Gale & Hist, 1966; Tungate, 2010). Watt's invention was a more economical option to the old Newcomb engines, as they substantially reduced fuel consumption. Oddly enough, they did not sell these engines for a direct price initially. Instead, they set up patents that yielded 1/3 of the fuel cost savings from their engine use compared to a Newcomb engine (Gale & Hist, 1966; Doty, 1998; Tungate, 2010). Watt's steam engines yielded a good deal of profit for Boulton, and he had a vested interest in securing the success of the companies that employed them, most notably, the Cornwall mines. Eventually, the Anglesey mines would prove a formidable competitor, and their ability to cheaply mine copper flooded the market and drove prices to the ground. As noted by Tungate (2010), the extra supply and unequal demand reduced Boulton's revenue from his steam engine business, and he became increasingly involved with the copper trade. In fact, it appears that Boulton purchased a large amount of copper from the Cornwall mines (Smiles, 1865). With such a massive investment in the copper trade, it makes sense that Boulton would pursue a coinage reform that would bolster business for the very mines that generated a sizable portion of his revenue (Margolis, 1988). At the same time, his involvement with the coinage reform would strengthen his reputation as a gentleman of the enlightenment (Tungate, 2010). Beyond the social advantages of his involvement with an English coinage reform and the protection of his revenue in the copper trade, producing a copper coinage for England would also benefit his many other business ventures (Cule, 1935). Any increase in his reputation and power from his involvement with coinage would likely result in residual effects for his other businesses and only serve to generate more income. All of these facts combined might suggest that perhaps Boulton's actions were less charitable than initially presented.

Regardless of his intentions, there was a real need to curb the rampant counterfeiting issue that plagued the English people, and Boulton was more than willing to rise to the occasion. The same year that Boulton had the idea to apply the power of steam to minting remains unclear, but we do know that by 1787 the idea became more than a dangerously fleeting fantasy (Doty, 1998; Clay & Tungate, 2009). An English coinage reform seemed all but inevitable, and Boulton was already gaining experience in the minting business. He received a contract to produce coinage for Sumatra. This venture allowed Boulton to fully understand the minting business's complex nature and the multifaceted operation that it necessitated (Doty, 1998). This experience was marked by slow production and the reliance on too many people outside Boulton's direct purview. In short, the Sumatran coinage tempered Boulton's zeal and made him painfully aware that he lacked the requisite skills and resources to manage the production of an entirely new coinage for England. The Sumatran coins were uninspired and far from a marked improvement on the abilities of the Royal Mint. Furthermore, they were not struck using steam and were just as susceptible to counterfeiting. There would be no point in trying to secure a contract with a product that made no notable improvement on the very issue that triggered the coinage reform. Steam power could help address the production rate, but he would need a better way to combat counterfeiting. DROZ EDGE LETTERING |

At this point, Boulton was already making concrete plans to apply steam power to his minting operations, but he still lacked the artistic talent that he sought. Through his meticulous records, we can see that at least one very talented engraver had captured his attention, Jean Pierre Droz. They first met in December of 1798 when Boulton, Watt, and Thomas Jefferson visited Droz in Paris to see a demonstration of his latest invention (Pollard, 1968; Doty, 1998). He had built a contraption that allowed for the application of either raised or incuse edge inscriptions while coins were being struck. This new method had several distinct advantages over the standard practice of the time. First, it reduced the overall production by combining the edge inscription and striking process into one step. Second, the edge inscriptions were often more pronounced and made the coins more difficult to counterfeit. Third, the device produced a coin with a standard diameter, which also dissuaded counterfeiting. And finally, it allowed for a degree of production consistency that was unmatched at the time. In short, the new method developed by Droz was what Boulton was hoping to do at the Soho Mint. If he could combine Droz's work with steam power, he would be able to mass-produce a coinage of unprecedented quality. To say the least, Boulton was impressed, and he soon offered Droz a prominent position at the Soho Mint (Doty, 1998; Selgin, 2011). The bond between the two men was undoubtedly strengthened by their mutual desire for a coinage reform in their respective countries. Droz was adamant about a French coinage reform, and Boulton was in the process of soliciting one for England. Of course, as Boulton would eventually find out, first impressions are not always quite what they are thought to be. While Droz entertained Boulton's offer, Watt and Boulton eventually returned to England, where Boulton's true work awaited him.

An English coinage reform ordered by the Ministry of William Pit seemed imminent, and Boulton was doing everything he could to aid his efforts to secure a contract with the government. However, Boulton was not without competition. According to Doty (1998), Thomas Williams also had his heart set on securing a coinage contract for England. The two men were not strangers. Thomas Williams was the proprietor of the Anglesey mines that were the most prominent domestic competitor to the Cromwell mines that Boulton was intimately connected to (Tungate, 2010; Margolis, 1988). Boulton was also well aware that Williams was already producing copper tokens far superior to anything he could make. This might lead one to argue that Boulton was at a disadvantage, but he had two secret weapons that Williams lacked, steam power and the new method developed by Droz. The issue was that Williams was also seeking Droz's employment, a fact that Boulton was well aware of and led to a large degree of insecurity between Droz and Boulton (Pollard, 1968; Doty, 1998). For better or worse, Droz kept to his arrangement with Boulton. 1788 DROZ PATTERN ½ PENNY |

Droz remains in Paris but has seemingly agreed to help Boulton secure his coining contract provided Boulton fairly compensates him for doing so, a detail that Boulton attended to generously. The first correspondence between the two occurs in early April when Boulton sent Droz sketches of George III and steel to produce dies to strike shilling size silver pieces that would aid his lobbying efforts (Pollard, 1968). Boulton was no stranger to lobbying, and his efforts to establish an assay office in Birmingham in the 1770s afforded him much experience and several invaluable connections (Robinson, 1964; 1963). Droz would reply on April 14th, 1787, requesting a life-size plaster mold of the King and inform Boulton of a new method he was developing to add edge inscriptions (Pollard, 1968; Doty, 1998). This typical back and forth communication continues, and with each letter, Boulton expresses increasing anxiety about obtaining the patterns from Droz. Eventually, Boulton would try another tactic. If he couldn't get Droz to deliver the pattern pieces, perhaps he could persuade Droz to produce his press sketches, allowing further development to occur at Soho. The terms for the sketches were settled, and Boulton impatiently waited. A clear pattern emerged, Boulton would request something from Droz, and in return, Droz would demand more money (Doty, 1998). All of this eventually came to a head, and Boulton insisted upon Droz's presence at Soho, which resulted in him visiting in September of 1787. Although the trip ended in October, it seemed to reassure Boulton, and he soon placed an order for two large coining presses and a single small cutting press (Doty, 1998).

While Boulton worked diligently through November in Birmingham to build a structure to house his new mint, Droz continued his usual antics and avoided producing anything useful. Despite Boulton's numerous requests and supplied material Droz failed to deliver the pattern pieces or the sketches for his presses. This nearly spelled disaster for Boulton, as the Lords summoned him on the Committee of Coin on December 10th, 1787 (Doty, 1998). As fate would have it, Boulton was ill, and the Lords agreed to postpone the meeting until the first week of January. Eventually, Boulton met with the Privy Council. Despite the odds being stacked against him (e.g., no patterns to show, his presses were not constructed, and his only argument was based on what he "could" do), he managed to defeat Thomas Williams and seemingly convince the Lords to that he was the man for the job. This was great news, but Boulton had made several grand promises to the council. According to Doty (1998), he promised eight cutting presses and six autonomous coin presses would be built and connected to steam power by June 1st, 1788. However, the issue was that Boulton was still waiting for, among other things, the sketches for the new presses from Droz. Despite the flurry of activity at Soho in the early months of 1788, Boulton needed the sketches to progress forward. Droz was so despondent to Boulton's request that the latter had no choice but to send his son (Matthew Robinson Boulton) and a trusted colleague, Andrew Collins, to oversee Droz's work (Doty, 1998). This proved fruitful, and Droz produced a dozen or so gilt pattern halfpenny pieces at the end of February and sketches of the presses by the end of March. From what I can gather from Doty's book, this was the most work that Boulton was able to secure from Droz up until this point. Boulton, reassured by Droz's work, realized that he needed to secure him in England if he ever hoped to benefit from his skills. Doty (1998) notes that Boulton sent him a letter in May of 1788 requesting his relocation to Birmingham. Droz seemingly agrees but predictably postponed his trip.

The following month marked a dark time in the early history of the Soho Mint. Although Droz managed to produce another 54 gilt pattern halfpennies, they were struck by hand, suggesting he was having trouble with his new press (Doty, 1998). Despite this seemingly important detail, Boulton was eager to lobby for a coinage contract, and the new patterns would be an excellent tool to use. From most accounts, the patterns seemed to make quite the impression, which was both a blessing and a curse. Doty (1998) notes the specimens were of such exceptional quality that Royal Mint officials objected to the possibility of a private citizen producing them. In short, the Royal Mint officials were threatened, and if Boulton were to succeed, it could put them in a precarious situation (Martin, 2009). To make matters worse, the King soon fell ill, and the Lords of the Committee were in no rush to approve a new currency when they unsure whose effigy it needed to depict (Doty, 1998; Selgin, 2011). Undeterred, Boulton continued lobbying to no avail. As if things were not already complicated enough, Droz decided in October 1798 to finally give into Boulton's earlier requests and move to Birmingham, which was a near disaster. Droz and his entourage had no issue clearing customs, but Droz's suitcase shared a different fate. Suspicious Royal Mint officials seized Droz's suitcase, which contained his secret new collar device that played a crucial role in building Boulton's case to secure a coinage contract. Luckily, the Royal Mint officials overlooked the collar, and his luggage was soon returned (Pollard, 1968; Doty, 1998). The more significant issue was that Droz was finally in England, but Boulton had next to nothing for him to work on. Boulton already found himself in a perilous financial situation, and the added strain of paying Droz's salary without a way to recoup his money only served to make matters worse.

1789 GEORGE III RESTORED TO HEALTH |

The following year afforded a series of opportunities that Boulton took full advantage of. The early months of 1798 marked the King's recovery, and Boulton had a great idea. He decided to produce medals to commemorate the King's recovery (Pollard, 1968). This, of course, had several advantages. It provided something for Droz to work on, it provided the workers at Soho much-needed experience, and the new medals could serve as a representative of Soho's capabilities. It seems as though the medals were a success, and the first batch sold in April with production running until the end of June (Doty, 1998). Finally, Boulton was able to profit off Droz's employment, but this was a short-lived victory. Although the medals made good impressions on the right people, there was still too much opposition to Boulton's proposal. No further developments would occur for some time.

During the rest of 1798 and through the end of 1790, the Soho Mint would experience a long series of ups and downs. Droz would return to his despondent ways, which took a heavy toll on his relationship with just about every prominent figure at Soho. Boulton, fed up with the inadequacy of Droz's work ethic, was aware of the fact that Droz was unlikely to be of much help; however, a looming contract to produce regal copper coinage for England unscored Boulton's perceived reliance on Droz. After all, it was the pattern pieces with the edge inscription that so thoroughly impressed the committee. Boulton made one last attempt to secure and motive the services of Droz. No contract was established between the two men until this point, but this changed in November of 1790 (Doty, 1998). For better or worse, Boulton and Droz were linked by contract for two more years. The new terms required Droz to complete the master dies for the pattern pieces, train workers to engrave the collar pieces, and produce the die-cutting lathe. Not surprisingly, he failed to complete any of these tasks (Pollard, 1968). After arbitration, Droz was eventually dismissed, marking the departure of one of Soho's most prominent villains.

On a more positive note, a great deal of progress was made on the machinery in 1789, which allowed Boulton to file a patent for the steam-powered press on July 8th, 1790. Doty (1998) speculates that Boulton likely filed this patent application to dissuade any future attempts by Droz to claim the invention as his own. As we will see, Droz was not above attempting to commit intellectual theft, but that is a story for later (for more information view the item in this set titled "1801(03) Spain Droz Fraud Medal Skinner Collection". As it turns out, Droz's new collar was of little consequence after the leading engineer at Soho, James Lawson, devised a one-piece rising collar. Doty (1998) noted that the engineers improved the number of blows each machine could make from 40 per minute in June to 55 by early July. At the same time, they managed to build another press and figured out a way to improve the life of dies. Despite all of these technical advances, they were useless without securing contracts to produce coins, tokens, or medals. During 1791 the Soho Mint would strike coins for Bombay and tokens for numerous outfits, but the little money earned from this sporadic business was not covering the expenses (Doty, 1998). A series of unfortunate events would eventually place a further financial strain on Boulton, and he had no choice but to dismiss a substantial portion of his workers toward the end of 1791.

Luckily, 1792 would prove a little more promising for the Soho Mint. The French Revolution paved the way for Boulton to secure a contract with the Monneron Brothers to produce numerous medals and token coinage for France (Jones, 1989). This was the first true test of Soho's capabilities, and by most accounts, it was not going well. Boulton's longtime rival, Thomas Willaims, was cornering the available supply of copper, and this made production difficult enough for Boulton, but this issue was just the beginning. As it turns out, the 5 Sol pieces were so large and thick that the recoil reduced production speed to 45 blows per minute (Doty, 1998). Boulton struggled to stay current with proposed timelines, and the slow production delayed payment for his work, furthering his financial strain (Margolis, 1988). It is no secret that the Soho Mint nearly ruined Boulton financially. Droz singlehandedly cost him more than £3000, which is nothing compared to the £9000 he had paid for other mint related expenses all in just four years (Doty, 1998). According to the Bank of England's inflation calculator, this equates to £1,822,880 ($2,357,074) today. Feeling the pressure of his financial hardships, Boulton, at one point, actively sought to sell his mint to either the Monneron Brothers or the French government (Margolis, 1988; Doty, 1998). Luckily for us, Boulton was unsuccessful in his attempts, and the Soho Mint lived to see another day. The technical and financial issues would continue to plague the Soho Mint, but through the sporadic profit from foreign coinage contracts, striking medals, and domestic tokens, the Soho Mint persevered.

Throughout the early years of the Soho Mint, several hard lessons were learned, all of which undoubtedly influenced its success. Producing the 5 Sol coins for the Monneron Brothers was a real challenge for the Soho Mint, even after several years of minting experience and countless technical improvements. Doty (1998) argued that had Boulton secured an English coinage contract, he would have been woefully underprepared to fulfill it, and this would have undoubtedly tarnished his otherwise fine reputation. In essence, the long series of delays (e.g., Droz's unwillingness to work, technical difficulties, skeptical Royal Mint officials, the King's bout of madness, and the unmotivated Lords of the Committee on Coin) eventually would prove to be a blessing in disguise. Despite all this hard-earned wisdom, Boulton and his Soho Mint still had a long and bumpy path ahead of them.

Success, inadequacy, and overkill:

As the title might suggest, Boulton was eventually able to secure a contract with the English government, but it was far from a smooth journey. Unlike Boulton's past misinterpretations, a contract to strike English copper was all but a given by the Winter of 1797 (Doty, 1998; Dyer, 2002). As before, Boulton did not miss a beat and traveled to London to lobby for the process to pass through the bureaucratic red tape that held it back for so long. It appears the project had hit full steam by the 3rd of March, 1797, which is supported by a letter from Lord Liverpool to Boulton, essentially notifying him that he had been awarded the contract (Doty, 1998). Despite this promising communication, Boulton would not receive the official patent until June, a detail Boulton did not fully foresee. Much work remained to be done in London (e.g., find material, settle on the details for the designs, etc.), and Boulton remained there for some time. Boulton's attention to detail is the hallmark of the pieces that he produced. No detail was too small for consideration. This is evident in the feedback he provided on the designs to the engravers, requiring the smallest of alterations to fully satisfy his tastes and that of the Lords of the Committee on Coin (Tungate, 2010). Although some details of the new coinage were set by the government, Boulton did have leeway to express his prowess. For instance, the government stipulated the weight of the new coinage but made no restriction on the size of the pieces. Boulton took this opportunity to incorporate his own love of standardization. In a letter dated May 19th, 1797, reproduced by Prosser (1913), we learn that Boulton intended for his coinage to adhere to standard foot measurements. The letter details that eight twopence pieces placed edge to edge should measure exactly one standard foot according to the standard he obtained from the Royal Society. He made similar requests for pence (17 to 2 feet), halfpence (10 to a foot), and farthings (12 to a foot). While away in London, he left this task to John Southern, who by Posser's (1913) account was the most scientifically inclined worker at Soho at the time. SIZE COMPARISON OF CIRCULATING COINAGE |

Luckily, Boulton had a solid crew back in Birmingham that was more than capable of working in his absence. A Mr. Brown seemingly took the lead at Soho, and correspondence between him and Boulton underscores how anxious the latter was about the toll the new coinage would take on the machinery (Doty, 1998). The much-anticipated patent was not for the halfpence pieces Boulton had hoped and prepared for. Instead, the government wanted pence and Two pence pieces. These new coins dwarfed the Monneron 5 Sol tokens that nearly wrecked the Soho Mint years earlier, a fact that Boulton was painfully aware of. Doty (1998) noted that Boulton wrote to John Southern requesting that air pumps be added to counter the violent recoil that would undoubtedly occur. As one can see, the lessons learned from the Monneron contract were not soon forgotten (Margolis, 1988). Despite all of the improvements made, it seems that Boulton and his associates were not entirely confident that their machinery would be up to the task. Boulton had the idea of rebuilding his mint, but without a notable improvement to how the machines were connected to the steam engine, any change would do little to improve their chances of success.

Without a better option, Boulton went forward with his plans and put his mint to work on the 19th of June, 1797, striking pence (Peck, 1964; Doty, 1998). Boulton's fears would soon be realized. Among the numerous issues, perhaps the most concerning was noise. As Doty (1998) suggests, this may be a bit exaggerated, but numerous records indicate that the noise was unbearable and may have even caused the deafness of several workers. More than ever, Boulton realized he needed a new way to connect the presses to the steam engine. By some miracle, John Southern had a solution that made the entire operation smoother and reduced many of the issues that plagued the Soho Mint. With a solution to the problems in hand, it suddenly made sense to build an entirely new mint incorporating the revised technology, thus giving rise to the second Soho Mint. From the records provided by Doty (1998), it appears work on the second Soho Mint started the 1st of April, 1798, and continued until the winter of 1800, with the bulk of the work being completed in 1799. It appears the second Soho Mint was fully operational by May of 1799, but this was a slow and complicated process. The new presses were built and temporarily set up to strike pence in the old mint to keep up with deadlines. Once the new two-story structure was erected and the steam engine settled on the second floor, the new presses were moved in waves to the new complex. The first two presses were fully operational in the second Soho Mint by late February of 1799, with two more joining in early March, and the remaining four by the 1st of May (Doty, 1998). A little wiser and perhaps even more determined than ever, Boulton had finally finished the mint that he aspired to build.

The 1797 patent detailed that a total of 500 tons of copper pence and twopence pieces were to be struck, with 20 tons being delivered each week (Doty, 1998). Despite all of the difficulties, Boulton mostly managed to keep good to his timelines. The first delivery arrived in London on the 26th of July, 1797, and an official announcement was made denoting the new coinage as legal tender (Doty, 1998). Pence were struck through 1797 and 1799, but twopence production did not begin until January of 1798 and was complete by April. Oddly enough, through a series of unofficial renewals of the original 1797 patent, another 20 tons of twopence would be struck in early 1799 (Doty, 1998). By the end of this contract and the two renewals, a total of 43,969,204 pence and 722,180 twopence were struck for a total of 44,691,384 coins. Supposedly, the working dies were destroyed on the 26th of July, 1799, under the supervision of the assigned Royal Mint comptroller Joseph Sage marking the official end to the production of pence and twopence pieces (Doty, 1998). The second Soho Mint proved efficient, and this created another set of issues. A new contract for English copper was not likely in the foreseeable future. The Mint's efficient production made it unlikely that the old and new contracts would ever overlap. With Boulton's finances still recovering from Soho's formative years, and the lack of reliable income flow from the mint, he had little choice but to lay-off a sizable portion of his roughly 140 mint employees (Doty). This would be a general pattern that would repeat until 1803 when business at the Soho Mint would boom. 1799 Proof Farthing |

As proud as Boulton must have been to produce pence and twopence pieces, his real ambition was to strike halfpence. After all, the halfpence had been the workhorse driving the wage-based pay of the working class. Furthermore, the halfpence were the target of choice for the counterfeiters. Perhaps if Boulton were allowed to strike halfpence of the same quality as the pence and twopence pieces, it would mostly resolve the ever-growing issue of lightweight counterfeits. Not to mention, Boulton already had preparations in place to strike both halfpence and farthings. By May of 1799, it appears that Boulton had devised a new design for the halfpence and farthings. As detailed by Doty (1998), Boulton notes that the wide rim found on the pence and twopence pieces would be reduced, the field would be curved to help protect the higher relief points of the design, and an oblique pattern would be impressed on the edges of the coins before striking them in a collar. Reducing the broad raised rim would help facilitate the striking process and reduce the toll it would take on the presses, a hard lesson learned from their first English contract plagued with ongoing issues and delays. Perhaps it was Boulton's prior experience that led him to technically break the law. Yes, you read that correctly. The well-mannered, morally sound, and patriotic Boulton technically broke the law. Correspondence between Boulton and John Southern indicates that all eight presses were in operation at the second Soho Mint by the 1st of May of 1799 (Doty, 1998). The letters further detail that six presses were striking pence, one press was striking halfpence, and the final striking farthings. Production of the halfpence and farthings was suspended during the first week of May due to a high profile political visitor, but it appears it was resumed, and some 20 tons of halfpence and farthings were struck by the 20th of August, 1799. Although The Lords on the Committee of Coin invited Boulton to make a formal proposal for halfpence on the 17th of August, 1798, he wouldn't receive the official green light until the 4th of November 1799 (Doty, 1998). Under the current laws, his clandestine minting operation would have been highly illegal, and I can only imagine the history of the Soho Mint would be different had the suspicious Royal Mint officials discovered what Boulton was up to.

Boulton's secret remained safe, and official production of 550 tons of regal coppers with the ratio of 10 halfpennies to each farthing commenced on the 10th of November 1799, with the first shipment scheduled to occur on the 18th of November (Doty, 1998). The improvements made when building the second Soho Mint proved highly efficient, and little trouble occurred while fulfilling this new contract. The Soho Mint was able to finish the second contract by the 18th of July, 1800, and in total, 46,704,000 coins were struck, 42,480,000 halfpennies, and 4,224,000 farthings (Doty, 1998). Between 1800 and 1802, the Soho Mint witnessed a return to the boom or bust state from the mint's formative years. It would be several more years before Boulton would again be asked to strike copper coinage for England, but he found work striking coins for numerous foreign countries. Between 1800 and 1805, the Soho mint would produce coins for numerous countries such as Sumatra, Isle of Man, Ceylon, Presidency of Madras, Bombay, and Ireland.

NEW SECURITY EDGE OF THE 1799 COINAGE |

The Isle of Man coinage, to some extent, was a byproduct of the 1797 English contract. It appears that John, Duke of Atholl, was so impressed with the large pence pieces that he wrote a letter to the King requesting that Boulton, instead of the Royal Mint, produce the new coinage for the Isle of Man (Doty, 1998). The Royal Mint had fulfilled the island's needs in 1786, and although those coins were a marked improvement upon their English counterparts, they were still far inferior compared to what Boulton was able to produce. It would be nearly two more years before Boulton received the official patent. In the meantime, Boulton put Küchler to work preparing the new dies. Doty (1998) noted that the obverse design allowed him to recycle the bust of George III used on the 1797 coinage, but the considerably smaller size presented some difficulty. The reverse design was entirely new. Britannia was replaced with the triune and triskele, and the English motto was replaced with the Manx motto (Nelson, 1899). From most accounts, production began on the 4th of March, 1799, and in the end, some 94,8282 pence and 194,376 halfpence were produced for a total of 289,204 coins (Doty, 1998; Tungate, 2010). The new arrivals were popular, and another order was placed in 1813. This second contract was shipped on the 15th of June, 1813, and consisted of another 99,400 pence and 98,308 halfpence (Doty, 1998). This would mark the final chapter for the Soho Mint and the Isle of Man.

A few years after the conclusion of the first Isle of Man contract, the East India Company approached Boulton seeking a coinage for its newly acquired territory, Ceylon. By this point, the Soho Mint was a well-oiled machine, and the contract was fulfilled by the 29th of May, 1802 (Doty, 1998). The Ceylon coinage's quick production and delivery must have made a rather large impression on the East India Company's authorities, as they soon placed an order for their other territory, the Madras Presidency. As it turns out, the East India Company had been trying to secure a contract with Boulton since the early months of 1800, but Boulton was entirely too busy with his domestic obligations to seriously consider it (Doty, 1998). Eventually, this would give rise to a massive order for copper coinage. The only catch was that the obverse and reverse would be entirely different than anything else produced at Soho. The obverse would depict the East India Company's arms and motto, while the reverse would contain the denomination in both Persian and English. The latter detail was more complicated, as the East India Company would have to provide a consultant to make sure the inscriptions were correct. The consultant's name was Dr. Wilkins, and by most accounts, he was a perfectionist that made the engraver's job very difficult (Doty, 1998). Although caught in the crosshairs of Dr. Wilkins and Küchler, the engraver John Phillip (the same one rumored to be Boulton's illegitimate son) managed to produce ready dies by October of 1802. Production began shortly after, and by the end of May 1803, a total of 37,926, 576 were struck and delivered (Doty, 1998).

Boulton was able to produce and ship the Madras coinage with such efficiency that it should be of little surprise that the East India Company would call upon the Soho Mint to produce coinage for the Bombay Presidency. According to the East India Company records provided by Stevens (2019), copper coinage production in Bombay was not only expensive, but the machinery the locals had at their disposal was entirely too inadequate. To this end, it would be cheaper and more efficient to import copper coinage from England. The company's arms and logo appeared on the obverse, much like the Madras coinage, but the reverse was slightly different. Balanced scales would be depicted on the reverse with the Persian legend "Adil" separating the two pans, and the date would occur immediately below in Arabic figures (Stevens, 2017). The obverse design was justified as these coins were expected to freely circulate in Bengal and Bombay, both of which were under the authority of the East India Company (Kalra, 2013: Stevens, 2019). This new design must have been somewhat of a relief for Phillips. The shorter Persian legend likely required less tutelage from Dr. Wilkins and a greater ability to avoid Küchler. Once complete on the 28th of April, 1803, a total of 12,240,550 were struck for Bombay (Doty, 1998). The relationship with the East India Company provided much-needed work for the Soho Mint and, to some extent, marked the beginning of the mint's busiest period.

The next most significant coinage contract for the Soho Mint would be a little closer to home. Ireland was in desperate need of a new coinage, and talks started as early as 1804, but not surprisingly, the government was slow to act. It wasn't until the 26th of March of 1805 that Boulton was finally permitted to move forward with a new coinage for Ireland (Doty, 1998). The new coinage would be similar to their English counterparts. The obverse would be the same as the 1799 English coinage; the denominations would be the same, albeit slightly lighter. Perhaps the most notable change was the reverse. Britannia was replaced with a harp. Given other obligations at the time, production was slightly delayed until April. In the end, a total of 8,788,416 pence, 49,795,200 halfpence, and 4,996,992 farthings were struck for a total of 63,580,608 new Irish copper coins (Doty, 1998). Oddly enough, Boulton seemed to take particular pride in this contract and even placed it before starting the third run of English copper. 1805 IRELAND PENNY |

The third and final English contract was far from immune to the issues that delayed the prior coinage. The Lords of the Committee on Coin were indecisive, and the bureaucratic process proceeded at a snail's pace. Nonetheless, Boulton was asked to submit a formal proposal on the 20th of November 1804, to which he responded six days later (Doty, 1998). It appears that some confusion occurred that further delayed production, but eventually, matters came underhand, and work began. Production did not officially start until the 20th of March, 1806, with farthings taking precedence over pence and halfpence. Accordingly, Doty (1998) reports that by the 31st of March, 4,833,768 farthings were delivered and 19,355,480 pence closely followed that in May, and 87,893,526 halfpence by the end of June. Production of farthings, halfpence, and pence continued into 1807, yielding an additional 1,075,200 farthings, 41,394,384 halfpence, and 11,290,168 pence. The mass production seemingly overwhelmed distribution efforts. In fact, it appears that the distribution of the third English contract was not complete until 1809 (Doty, 1998). Once production had stopped, a total of 165,842,526 new copper coins had been released into circulation, leading to a glut in copper coinage.

The rise and fall of the 3rd Soho Mint:

The last English copper coinage produced by the Soho Mint was distributed in March of 1809, just four months before the passing of Matthew Boulton on August 17th, 1809 (Doty, 1998). I think it rather fitting that the elder Boulton held on long enough to see the job through to the end. Up until this point, his son, Matthew Robinson Boulton (hereunto referred to as Matt) along with his partner James Watt Jr., ran the day to day operations of the Soho Mint. As such, it seems natural that Matt would petition the Lord of the Committee on Coin to continue production of copper coinage for England on July 27th, 1809 (Doty, 1998). Not surprisingly, this request was denied. The public was saturated, and the copper coinage crisis had been completely relieved. Furthermore, Boulton's persistence ensured that the Royal Mint purchased a steam-powered mint from him, eliminating the need for Soho Mint. It would make little sense for the government to pay a private contractor for work that they were now more than capable of themselves. The English government's reliance on the Soho Mint was dissolved, and Matt would never have the opportunity to rebuild it.

The Soho Mint's fate now rested in Matt's hands, who, by most accounts, seemed less than enthusiastic about continuing the family business. It seems as though without the help of James Watt Jr., the Soho Mint, would have essentially been out of work between 1810 and the early 1820s (Doty, 1998). During this time, the Soho Mint would produce copper planchets for the United States, Brazil, and Portugal. Except for a small order for the Isle of Man in 1813, the Soho Mint did not secure any notable coinage contracts. This lack of activity took a financial toll on Matt, and he could not afford to continue paying the bills. He eventually decided to sell the Soho Mint and began looking for buyers. In the meantime, Watt secured a contract to strike coins for St Helena, which was completed in June of 1821. Around this time, the East India Company had expressed interest in purchasing the Soho Mint, and the St Helena coinage served as a demonstration for the potential buyers. It took them some time to decide, but they agreed to purchase the mint on February 13th, 1823 (Doty, 1998). During this time, the Soho Mint was engaged in producing copper coinage for Buenos Aires, which was an extension of a prior contract. Once production was complete, the mint was dismantled, and by August of 1823, the process of taking it down and packaging it up was mostly complete.

1830 GUERNSEY DOUBLE |

Finally, Matt was rid of his father's mint, and he could instead spend his time with his family and engage in leisurely activities, or so it would seem. Given the prior two contracts with Buenos Aires, it was logical to think that a much larger order was to come, and it seemed as though Columbia might also require coins and a mint (Doty, 1998). This would have been perfect for Matt as he could construct a new mint, strike coinage for both Buenos Aires and Columbia, and then sell the newly constructed mint to the latter. Construction began in 1824 and continued until it was halted in 1826. Buenos Aires and Columbia's political climate had deteriorated, and it seemed unlikely that the coinage contract was to follow from either country. The third Soho Mint remained unengaged and unfished for several years until 1830. In November of 1830, the mint managed to complete a small order of coins for Guernsey without steam. This might seem odd, the third Soho Mint was not fully operational with steam power until June 1831, and even then, it was half the size of its predecessor (Doty, 1998). Had it not been for the impending contract to produce many tokens for Singapore, the third Soho Mint might never have been powered by steam. Under Matt and Watt Jr.'s direction, the third Soho Mint was eventually successful in striking coins and tokens for Guernsey, Chili, Singapore, and the Lower Bank of Canada. This success lasted until Matt passed in the summer of 1842, and the fate of the Soho Mint once again was in danger.

At the time of Matt's death, his son Matthew Piers Watt Boulton (hereunto referred to as Piers) was too young to run the family business. In his place, three trusted advisors, Joseph Westley, Thomas Jones Wilkinson, and Charles James Chubb, would determine the fate of the third Soho Mint. At first, it seemed as though it would be sold, and several potential buyers arranged in-depth inspections of the facility in 1842, but both deals fell through (Doty, 1998). With little other options, the advisors decided to run the Soho Mint themselves. Luckily for them, Piers came of age on September 22nd of 1843 and joined them in the decision making process. As noted by Vice (1995), Piers opted to keep the mint operating to increase its marketability. The financial toll of operating a mint eventually hit Piers, and he opted to sell the entire mint at auction. The third Soho Mint would be cataloged and auctioned off on the 29th and 30th of April, 1850. Once vacant, the buildings were rented out until they burnt to the ground in 1863 (Doty, 1998). Although this may mark the last chapter of the Soho Mint's history of striking coins, the story is far from over.

A lasting impact:

Boulton's Soho Mint was able to rapidly produce high-quality copper coinage that would stand the test of time and ultimately meet the general public's needs. It would be difficult, if not impossible, to refute the accomplishments of the Soho Mint. Still, some may wonder if his coinage did curb counterfeiting that had plagued England for centuries. To address this, we must first revisit the pence and twopence pieces of 1797. Despite the lack of edge lettering, the new pence and twopence pieces did have some features that would deter counterfeiting. For one, the coins were well made and noticeably more massive than any other circulating regal piece. Their expansiveness allowed for the possibility of wide raised rims which contained the incuse legend. The large raised rims would help protect the primary devices from excessive wear, and the incuse legend assured it would survive long after the raised rims wore down. All of this is to say that for counterfeits to pass, they would have to be of much higher quality, which would likely translate into less profit for the counterfeiters. Although not the intent of Boulton, there was another factor that protected at least the twopence pieces. As it turns out, the general public was not very fond of them (Selgin, 2011). They were enormous and heavy (i.e., 41 mm and 2 ounces) and were too bulky to carry around in any quantity. Because of this, they tended to build up in storekeeper's drawers, but the storekeepers had no real way of exchanging them for paper money or silver. All of these factors made them unpopular and therefore were less susceptible to counterfeiting.

1797 LIGHTWEIGHT COUNTERFEIT PENCE |

The Pennies were also rather large and heavy (i.e., 36 mm and weighed an ounce), but they were better received than their larger counterparts and circulated in excess of the next 65 years (Dyer, 1996). This made for an ideal target for counterfeiters. The large raised rims, incuse legend, and high quality did not prove sufficient to curb counterfeiting, as it turns out (Ruding, 1799; Ruding, 1819; Doty, 1998; Selgin, 2003). Individuals could collect genuine examples, melt them down, and make lightweight pieces. The excess copper from this process would yield substantial profit. Although this never became a widespread problem, it contradicted Boulton's claim, and he had a vested interest in curbing the issue. Most notably, he wished to secure future contracts to strike regal English copper, and this counterfeit issue could prove a considerable hindrance. Boulton was so concerned that he announced a 100 guinea payment for actionable information about the counterfeiters (Doty, 1998). As detailed by numerous sources, this led to a man named William Phillips to come forward with information about three counterfeiting outfits located in none other than Birmingham (Dickerson, 1936; Peck, 1964; Selgin, 2011). Boulton acted on this information, which eventually led to numerous arrests.

Although some of the earlier pieces were low-quality casts that were easily identified, the counterfeits became quite sophisticated as time went on. As noted by Clay and Tungate (2009) and further substantiated by Selgin (2011), the shallow designs proved to be much easier to reproduce than Boulton thought. Soon counterfeiters were engraving dies and striking pieces that were close replications of the actual coins despite the use of hand-operated presses. For those of you interested, Dickerson (1936) gives a full unabridged replication of the letter Boulton sent to the Lords of the Committee on Coin, which details the simultaneous raid on three separate counterfeiting facilities. However, so far, the focus of the counterfeits discussed were products created from fake dies. Peck (1964) notes that some counterfeits were produced using genuine dies that were stolen from the Soho Mint. He makes this argument based on the die diagnostics of the pieces he observed. I have full confidence in his conclusions; however, I have had no luck finding additional information on this topic. He even mentions that the origin of these struck counterfeits using genuine dies remains a mystery.

1806 LIGHTWEIGHT COUNTERFEIT ½ PENCE  |

An odd discrepancy to this point comes from Doty (1998), who points out that the working dies for the pence and twopence pieces were destroyed under the supervision of a Royal Mint official on July 26th, 1799. Of course, this does not preclude the possibility the dies were stolen before being destroyed. I have no answers to this problem, but I plan to continue digging. Peck (1964) mentions that the pieces were struck on a light planchet that was roughly 1 mm thinner than usual (i.e., 2 mm instead of 3 mm) and weighed substantially less (i.e., about 19 grams compared to a full ounce). The weight alone is enough to give these coins away; however, the next biggest clue can be found within the legends which run into the rims. As noted, the genuine coins were designed to prevent this from happening. The struck pieces using the genuine Soho dies (i.e., Peck-1110) are rather good, and I imagine these readily passed as currency at the time. To take this one step further, I would not be surprised if these fooled some collectors who assumed they were well-circulated genuine examples. Although the lack of written record of other Soho produced English coinage suggests they do not exist, the 1806 contemporary counterfeit in my collection suggests otherwise. This is a relatively novel research area for me, but at the minimum, we can assume that others likely exist. Despite Boulton's claims, his coinage was not immune to counterfeiting, but this does little to deter from his undeniable legacy. Before his involvement, the counterfeiting issue was so prevalent that a Royal Mint report from 1787 estimates that only 8% of circulating copper was genuine (Peck, 1964). Although I do not have an estimated number to report, I would hazard to guess that this number was substantially higher after Boulton flooded the country with high-quality copper coinage. With the mass counterfeiting in England under control, the Soho Mint could turn its sights towards loftier goals, such as revolutionizing money worldwide.

The Soho Mint had provided high-quality copper coinage to numerous countries, that without doubt, helped to replace the counterfeits that freely circulated before a better alternative was provided. As impactful as the coins may have been to different locales, the importance of selling ready to strike mints was likely much more profound. Over the years, Boulton would prove pivotal in setting up revolutionary mints in countries like Russia, Denmark, India, Mexico, and Brazil (Doty, 1998; Kalra, 2013). It is one thing to supply a steady stream of copper coinage, but it is entirely different to provide each country with the ability to take charge of their coinage reforms. Boulton's willingness to share his invention with the world allowed other countries to curb counterfeiting and gain internal stability (Selgin, 2003). For England, Boulton was able to supply an adequate amount of copper coinage and help them set up a self-sufficient mint using his technology. Eventually, coins would be struck by the Royal Mint using the same technology that struck its predecessors under the direction of Boulton. The new technology was so useful that it would remain in operation at Soho well until the 1880s (Doty, 1998). Even upon its demise in April of 1850, the Soho Mint gave rise to further innovation. The giant machines erected by Matt were sold at auction to Heaton & Sons, who eventually established the Heaton Mint. They would go on to strike coinage for various countries for over a century.

In the end, Boulton set out to better the lives of his countrymen, but in reality, he managed to achieve much more. His Soho Mint and the steam-powered mints that he sold would go on to impact generations of people across the globe. As technology advanced, the use of steam power to mint coins became obsolete, but nearly every modern coin in circulation today can trace its ancestry back to work done at the Soho Mint (Tungate, 2010). So the next time you get a handful of change in return, take a moment to appreciate the long numismatic journey that allowed for their development.

Restrikes:

The Soho Mint would eventually produce some of the finest coinage of the era. This, paired with its fame, would eventually demand collectors' attention, both counterparty and modern (Tungate, 2010). It is no secret that Boulton spread proof "samples" of his wares to anyone of power who would have them, such as the 300 medals he sent to help ease the process of selling a mint to brazil (Gilboy, 1990). Notable patrons and devoted collectors of his coins, medals, and tokens included George III, Sarah Sophia Banks, the Duke of Portland, and Samuel Birchall (Tungate, 2010). He understood that placing a well-made and artistically pleasing coin in the hands of a potential buyer made an argument against his employment mute. In short, Boulton was a shrewd businessman, and he used his abilities to impress and subsequently attract new contracts for his Soho Mint. It should be of little surprise that doing so also made his coins, tokens, and medals all that more appealing to collectors. In the Soho Mint's early years, Boulton would fulfill request for older patterns and proofs for collector consumption (Peck, 1964; Vice, 1995; Doty, 1998; Tungate, 2010). This practice would eventually become obsolete as the mint became more engaged with large coinage contracts, but this did little to curb the collector demand. This demand and the unfortunate action of a family member would, regrettably, introduce restrikes to the collecting world. For clarity, the term "restrike" is used to denote a coin, medal, or token that was struck after Soho's demise by William Joseph Taylor, not to be confused with a "late Soho" piece which was struck at the Soho Mint at a later date than indicated on the piece (Peck, 1964). To trace the history of these "restrikes", we must first revisit the final years of the third Soho Mint.

1799 "RESTRIKE" 1/2 PENNY |

As I noted earlier, when Matt had passed away in 1842, his son Piers was too young to run the family business. As such, the will appointed the trustees to run it in his absence, and when he came of age the following year, he played an active role in the fate of the Soho Mint. Eventually, Piers would opt to sell it, and he left the task mainly to two of his trustees. The old myth poised that the trustees haphazardly discarded several dies with a batch of scrap metal purchased by Taylor at the auction in 1850 (Peck, 1964; Doty, 1998; Vice, 1995). I had little reason to believe that this version of the story was anything but true until a fellow collector pointed me in the direction of a well-written article by David Vice. In his article, he suggests a very different series of events. As it turns out, Piers' hands-off approach to the sale of the Soho Mint would spark a large amount of controversy and ill will between all parties involved. As noted by Vice (1995), he was unaware that any tokens, medals, or coins were to be sold at auction, much less any dies or punches used to strike them. He was blissfully unaware that almost 300 older medals were struck in the early months of 1850, leading up to the sale. His ignorance was partly due to his lack of involvement and the fact that he did not receive a copy of the auction catalog until after it had been published. Upon learning all of this information, Piers sternly objected, but there was nothing that could be done. The auction was right around the corner, and the catalogs had already been distributed to potential buyers.

Although Piers would be unable to prevent the auction from occurring, he could make several countermoves to prevent the four complete collections of Soho medals (page 13 of the auction catalog) as well as the dies and punches used to strike them from leaving the hands of the family. As it turns out, the nearly 300 medals struck in 1850 were produced using Piers' personal supply of copper, which meant that the newly made medals were rightfully his property (Vice, 1995). Their removal from the sale made it impossible for the four sets to be considered complete. Next, Boulton would turn his attention to the 235 dies and punches (Medals: 122; Pattern coinage: 113) that were to be auctioned off. Vice (1995) notes that Piers would appoint someone to bid on his behalf to acquire these through the auction. For all of his efforts, Piers managed to retain almost 2,000 dies and punches for numerous medals, tokens, and coinage. Vice (1995) reproduces a letter dated April 26th, 1850, in which Piers justifies his actions. In short, Piers claims that he acquired the dies to protect the legacy of the Soho Mint and the collectors of its products by retaining the dies and preventing restrikes from being made.

Had this been the case, then it would have been a very noble effort on behalf of Piers, but as pointed out by Vice (1995), history would tell a very different tale. Of the nearly 2,000 dies and punches that Piers managed to save, over 1,500 of them corresponded to currency issues for various countries. The trustees were very cautious to ensure that the dies used to strike circulating coinage did not make their way into the general public's hands. In fact, they intended to destroy them (Vice, 1995). Piers objected to this, and they subsequently passed to him for storage. This point makes it particularly troublesome that an auction would occur in mid-1780, containing many modern restrikes using currency dies. Given that the dies were under such close watch by Piers, it seems odd that somehow they managed to fall into private hands that would make nearly a 1000 restrikes of various denominations in several different metals. Perhaps this is the first indication that Piers' intentions may not have been as pure.

The second indication comes from a letter reproduced by Peck (1964) and Vice (1995) written on October 3rd, 1887, from James Henry to R. A. Hoblyn. In this letter Henry recounts, the story told to him by Taylor detailing the casks of dies filled with wax sent to him by Mr. Boulton (Aka Piers). Given light of the evidence, it seems clear that Piers did play some role in the restrikes of the Soho pieces that were produced. If nothing else, it seems clear that he enabled Taylor by giving him the dies that he used to strike countless numbers of restrikes over the remaining portion of his life. Of course, one could argue that perhaps Taylor's restriking operation was not as large as implied, but the evidence provided by Peck (1964) on page 614 would suggest otherwise. Vice (1995) points out that Peck's report details 804 restrikes for a single transaction. It seems reasonable that multiple such transactions took place.

Piers' unethical and hypocritical actions make him perhaps one of the biggest villains of the Soho Mint. By most accounts, his father and grandfather were decent, morally grounded men that ushered a new "standard" of minting. It is a shame that Piers did not follow in their footsteps, but I suppose knowing this bit of history only adds intrigue for those who pursue the wares of the Soho Mint and the byproducts of their tools.

A complicated classification:

At times, it can be next to impossible, if not impossible, to distinguish between proofs, patterns, and currency strikes struck at the Soho Mint and those produced by Taylor. As such, these pieces dubbed "Taylor restrikes" have only served to complicate further the study of the coins contained in this set. Although numerous attempts have been made, the gold standard was established by C. Wilson Peck in his 1960 publication entitled "English Copper, Tin and Bronze Coins in The British Museum 1558-1958," which was later revised in 1964. The Peck numbers listed alongside each coin in this set are pulled from the second edition of this invaluable work. Even Peck, with the numerous important collections and the British Museum's help, still struggled to differentiate the many patterns, proofs, currency strikes, and restrikes of the coins produced. He often notes that his classification is based on speculation, but every attempt was made to logically interpret the data at hand to be as accurate as possible.

The English Soho coinage can be classified as either Early Soho, Late Soho, or as a Restrike. Peck (1964) notes the term "early Soho" refers to coins struck at the Soho Mint on or before the date depicted on the coin. The term "late Soho" is reserved for coins struck at the Soho Mint, possibly after that date indicated on the coin. Although these coins were struck later, they are not classified as restrikes but rather as "late Soho" pieces. The term "restrike" denotes pieces that were not struck at the Soho mint but were instead struck by Taylor using Soho dies after the mint's demise.

Throughout the descriptions for each coin, I do my best to include Peck's classification and rarity in the first paragraph of the description. The edge details have been included as a separate section for each coin mainly because this can be a very helpful diagnostic. When available, I have done my best to include the number of examples graded by NGC and PCGS in each coin's notes section. The term "bronzed" is used frequently within this set, and it is essential that I first define it before its use. Bronzed pieces can be distinguished from their counterparts by the relatively grainy appearance of the devices. The bronzing process helped seal the surfaces of the coin and protect the color. It seems from many notes made by Peck this process occurred on the planchet before striking. The planchet was essentially wiped with a powder combination that left a layer of the material on the planchet.

The "other" products of the Soho Mint

There is little doubt that Matthew Boulton's crowning achievement for his Soho Mint was striking English regal copper coinage. After all, it was this ambition that gave rise to the mint and sealed its legacy. As crucial as this feat may be, it only addresses a portion of the Soho Mint's history. Throughout the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Soho Mints, a wide range of pieces were struck. These included coins, tokens, and medals. Within coin collecting circles, at least the ones that I have typically encountered in the past, the last two categories I just mentioned seem to be largely ignored in favor of the first. Although the tokens and medals are often discarded as "other" products, they provide historical detail about the Soho Mint and, at the very least, complement the history surrounding the coinage. To this end, I have recently built a new custom registry set entitled " The medals of Soho near Birmingham" to tell the story of the medals struck at the Soho Mint.

Tokens:

The registry set detailing the story of the tokens struck at the Soho Mint is a work in progress. I have the needed information contained within multiple pages of notes, but I have yet to find the time to formally write it up.

I hope you have enjoyed this journey and that having a better understanding of the Soho Mint's history will only deepen your appreciation of the pieces within this set. So without further delay, let's check out some coins, medals, and tokens!

References:

Brooke, G. C. (1932). English Coins from the Seventh Century to the Present Day. London: Methien & Co. LTD.

Clay, R., & Tungate, S. (2009). Matthew Boulton and the Art of Making Money. Warwickshire: The Barber Institute of Fine Arts.

Cule, J. E. (1935). The Financial History of Matthew Boulton 1759-1800. (Master's Thesis). Retrieved from University of Birmingham Research Archive.

Dickerson, H. W. (1936). Matthew Boulton. Cambridge: Babcock and Wilcox, LTD. At the University Press.

Doty, R. (1998). The Soho Mint and the Industrialisation of Money. London: National Museum of American History Smithsonian Institution.

Dyer, G. P. (1996). Thomas Graham's copper survey of 1857. Numismatic Journal, 66, 60-66.

Dyer, G. P. (2002). The currency crisis of 1797. Numismatic Journal, 72, 135-142.

Gale, W. K. V., Hist, F. R. S. (1966). Boulton, Watt and the Soho Undertakings. Birmingham: Museum of Science and Industry.

Gilboy, F. F. (1990). Misadventures of a mint - Boulton, Watt & Co. and the 'mint for the Brazils'. British Numismatic Journal, 60, 113-120.

Jones, M. (1989). Medals of the French Revolution. The Royal Society of Arts Journal, 137(5398), 640-646.

Kalra, M. (2013). The birth of the 'new' Bombay mint c. 1790-1830 — Matthew Boulton's pioneering contribution to modernization of Indian coinage. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 74, 416-425.

Margolis, R. (1988). Matthew Boulton' s French ventures of 1791 and 1792; tokens for the Monneron Frères of Paris and Isle de France. British Numismatic Journal, 58, 102-112.

Martin, M. (2009). Collecting Soho patterns and proofs. Numismatic Circular, 107-118.

Nelson, P. (1899). Coinage of the Isle of Man. The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society, 3(19), 35-80.

Peck, C. W. (1964). English Copper, Tin, and Bronze Coins in the British Museum 1558-1958. London: The trustees of the British Museum.

Pollard, J. G. (1970). Matthew Boulton and Conrad Heinrich Küchler. The Numismatic Chronicle, 10, 259-318.

Pollard, J. G. (1968). Matthew Boulton and J.-P. Droz. The Numismatic Chronicle, 8, 241-265.

Prosser, R. B. (1913). The Boulton copper coinage. The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society, 13, 379-380.

Robinson, E. (1964). Matthew Boulton and the art of parliamentary lobbying. The Historical Journal, 7(2), 209-229.

Ruding, R. (1799). A proposal for restoring the antient constitution of the mint. London: Messrs Sewell, White, Egerton, Faulder, Wilkie, & Hatchard.

Ruding, R. (1819). Annals of the coinage of Britain and its dependencies, from the earliest period of authentick history to the end of the fifty-either year of the reign of his present Majesty King George III. London: Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor, & Jones.

Selgin, G. (2003). Steam, hot air, and small change: Matthew Boulton and the reform of Britain's coinage. The Economic History Review, 56(3), 478-509.

Selgin, G. (2011). Good Money Birmingham Button Makers, The Royal Mint, and the Beginnings of Modern Coinage, 1775-1821. Oakland, California: The Independent Institute.

Stevens, P. J. E. (2017). The coins of the English East India Company. Presidency series a catalogue and pricelist. London: Spink and Sons Ltd.

Stevens, P. J. E. (2019). The coinage of the Bombay Presidency a study of the records of the EIC. London: Spink and Sons Ltd.

Tungate, S. (2010) Matthew Boulton and The Soho Mint: copper to customer (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I.

Vice, D. (1995). A fresh insight into Soho Mint restrikes & those responsible for their manufacture. Format Coins, Birmingham, 3-14.

Recommended Readings:

Mason, S. (2005). The hardware man's daughter. West Sussex: Phillimore & Co. Ltd.

Mason, S. (2009). Matthew Boulton selling all the world desires. London and New Haven: Yale University Press.

McKnight, W. A. (1931). Power and Matthew Boulton. The Sewanee Review, 39(2), 170-189.

Robinson, E. (1963). Eighteenth-century commerce and fashion: Matthew Boulton's marketing techniques. The Economic History Review, 16(1), 39-60.

Smiles, S. (1865). Lives of Boulton and Watt principally from the original Soho Mss. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott and Company.

Uglow, J. (2002). The lunar men five friends whose curiosity changed the world. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

A few notes about my collection: