Set Description

|

This set is a tribute to my friend, Bill McKivor, who has since passed away. Although we only knew each other for a relatively short time, Bill quickly became one of my favorite people. He is the sole reason I ended up collecting the medals of the Soho Mint, and as such, it seems fitting that his memory lives on in my collection. Bill had an eye for exceptional quality, and although he handled most of the Boulton Family collection, the medals held a special place in his heart. I, too, have developed a keen fondness for the Soho medals, and so far, I have been successful in locating many examples paired with silver-lined brass shells. Several of them once resided in either the Boulton family or the James Watt Jr. collections. This set aims to build a top-notch collection of Soho medals, emphasizing the ones Bill held in such high regard. The pieces that comprise this collection have been carefully selected. When appropriate, I have included the relevant provenance for each piece and the historical significance of the event or person depicted on the medal.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

A tribute to Bill

|

Bill was a gregarious man with a warm personality, which allowed him to carry on a good conversation on almost any topic with almost any person. He had a way of telling stories that reframed dense history in a way that captured your attention and left you wanting to discover more. There were several instances in which I learned more from Bill than I did in any of my introductory history classes in college. He had a real passion for history which was probably only outshined by his passion for sharing his knowledge with whoever would listen. Bill and I spent hours talking on the phone about almost every topic imaginable, but most of what we discussed concerned the Soho Mint and its owner, Matthew Boulton. Like almost every other topic we discussed, Bill seemed to know things that I had only discovered through reading books from notable authors such as Richard Doty. Little did I know, Bill and Doty were very close friends, and given what I know about Bill and what I have learned about Doty, I would have greatly enjoyed the opportunity to have a conversation with them both. Talk about a power duo of awesomeness! On any note, during our first conversation, Bill detailed his journey of acquiring a significant portion of the coins, tokens, and medals from the Boulton estate. He always used to joke about being a paperboy across the pond buying the collection of a famed industrialist who revolutionized the minting of money. You see, Bill had a long and very successful career selling newspapers in Seattle and seemingly viewed himself as an everyday kind of guy. In reality, Bill was far from an everyday kind of guy. It is very rare to meet someone as genuine, kind, and forthcoming. Upon his retirement, he created a very successful business selling conder tokens, which gave rise to our friendship.

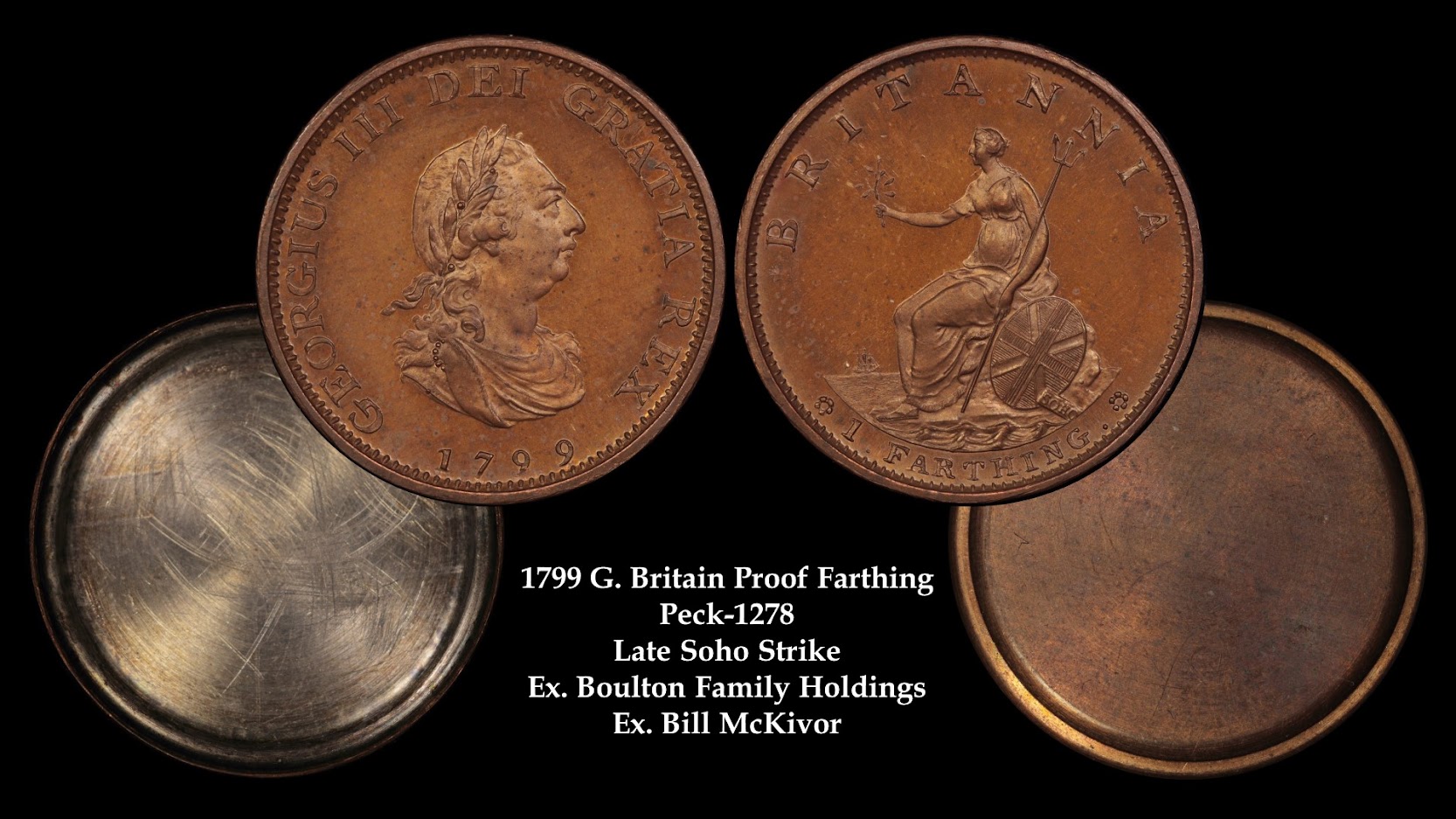

I had visited Bill's website in the past while doing some research on the Soho Mint several years before I contacted him. I remember being so impressed and intimidated by the seemingly endless photos of some of the most spectacular Soho pieces I had ever seen. Eventually, Bill listed a proof 1799 Farthing for sale contained in the original silver-lined brass shells and a provenance back to the Boulton Family. I took this opportunity to reach out and I ended up purchasing the coin from him. At the time, I did not have the funds to cover the entire purchase, but I wanted the coin. I provided numerous references and offered to pay a deposit and set relatively quick terms of payment. After all, I knew I could get the money; I just needed to sell a few extras to do so. Bill responded in his usual enthusiastic and easygoing way, telling me that the coin was mine and not to worry about the details. As I would later learn, Bill was far more concerned about getting the right pieces in the right collector's hands. For him, it wasn't about money. It was about forming connections with people and helping them along with their collecting journeys. In this way, Bill had a significant impact on me.  |

Bill was the type of guy who exuded knowledge. Like almost every other aspect, Bill was exceedingly generous with the information he had. I learned so much about the Soho Mint, Matthew Boulton, antique cars, tokens, and medals in such a short period of time. In one of our earlier conversations, I learned the exact day, and approximate time the ejecting collar was fully operational at the Soho Mint. A detail that I have yet to stumble upon in any of the numerous publications that I have read so far. It never ceased to amaze me how much Bill knew about seemingly obscure topics, such as the silver-lined brass shells produced at the Soho Mint. I spent months trying to research the topic on the internet with little luck, but within 30 minutes, Bill had provided me with enough contextual information to create a solid foundation for a short article. I hope to submit that article for publication soon, which I plan to dedicate in his honor. While discussing the silver-lined brass shells, Bill shared his passion for the medals produced at the Soho Mint, and this is the slippery slope that eventually led to my wallet becoming a bit thinner. He talked about the historical context of the pieces, and that proved to be my Achilles' heel. We discussed the vast array of art depicted on the Soho medals and the numerous nuances of collecting them. Bill piqued my interest, and that directly led to the construction of this collection. Had it not been for him sharing his passion, I would have almost certainly overlooked the medals and subsequently an essential part of Soho's history. His impact on me was not an isolated event. The most recent edition of the Conder Token Collector's Journal is a tribute to Bill in which numerous members shared their experiences with him, and it is truly amazing to see how many people he impacted from both a personal and numismatic standpoint.

Beyond Bill's willingness, if not insistence upon being helpful, he was a thoughtful and genuine person. This was abundantly clear when we talked about politics, religion, marriage, travel, or just about every other topic that one can think of. He had so many extraordinary stories to share that always seemed to highlight the importance of some life lesson. If I learned nothing else from him, it is always to be kind, and that life is what you make of it. He always encouraged me to grasp opportunities when they present themselves, which is what motivated me to start collecting medals. He piqued my interest, and he loved sharing his passion for them. What better excuse would I have for pursuing so many incredible pieces? Although Bill is no longer with us, his memory will forever live in my collection as I continue to pursue the coins, medals, and tokens produced at the Soho Mint.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

A few notes about this set:

For those unfamiliar with Matthew Boulton and his Soho Mint, I implore you to stop reading here and check out my original custom registry set, which provides the historical context needed to fully appreciate the significance of the pieces contained here. The current set aims to explore the social, economic, and artistic importance of the medals struck at the Soho Mint as it relates to the historical context of their production. I hope that the brief descriptions and detailed pictures will prove enjoyable for those wanting to learn more about the medals struck at the Soho Mint and those wanting to learn more about the events and people they depict. This set aims to include tidbits of historical context that might otherwise be overlooked. For instance, the title of this set is derived from the heading affixed to numerous pieces of contemporary communication between Matthew Robinson Boulton and officials at the U.S. Mint. I find the oddity of being so specific to state "Soho near Birmingham" humorous as most domestic correspondence to and from Boulton is simply denoted as "Soho".

While viewing this set, please keep in mind that several factors limit the breadth and scope of this pursuit. Perhaps the two most limiting factors are time and money in no specific order. I lack a reasonable amount of both. A good deal of time and energy has been devoted to assembling this collection, which has allowed me to include several pieces that once resided in the personal collections of either James Watt Jr. or the Boulton family. All of these pieces were purchased raw and subsequently graded with the appropriate provenance. These pieces are often some of the most well-preserved specimens in my collection and further attest to the care and pride that both families had for the Soho Mint.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

General introduction:

Although I wish I could provide a complete history of the medals produced at the Soho Mint, the fact of the matter is that I am still learning. For now, I plan to explore how the medals broadly fit within the context of the other Soho Mint products and explore how Matthew Boulton and his successors approached the business of striking medals. I can only imagine the knowledge that remains for me to discover. That said, if you have anything related to share, please feel free to reach out on the NGC forums. I love learning new things and making new friends!

What is a "medal"?

According to Frey and Salton (1973), a medal is a piece produced for the sole purpose of commemorating a historical event(s) or an award for personal merit. They are explicit that a medal is not produced to pass as money, but rather an item in which its value is derived from its historical and artistic merits. In this way, medals are a class of their own when compared to either tokens or coins. Given that Matthew Boulton's primary goal for building the Soho Mint was to propagate a coinage reform in his country, it seems odd that he would devote any energy to creating something that would not be a means to that end. This gives rise to a fundamental question – why did the Soho Mint strike medals? It is not a secret that Boulton, at least at first, did not see the value of producing medals. This fact is abundantly clear in his letter to Küchler dated March 13th, 1793, in which Boulton clarifies that he has neither the time nor inclination to oversee " the minutiae of such a minute business as making medals". To this effect, Boulton makes it evident that he views producing medals as a "lesser" task than striking coins, but as we will see, the medals played a vital role in the history of the Soho Mint, and it appears Boulton also realized their utility.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Why did the Soho Mint strike medals?

To address this question, we have to revisit the early days of the Soho Mint, which were marred by a seemingly endless array of setbacks and near catastrophes. Boulton would not be granted his first contract to strike regal copper coinage for England until March 3rd, 1797, but in the near-decade leading up to that event, Boulton was in a constant state of preparation that nearly cost him everything on more than one occasion. According to Doty (1998), Before the first Pence was struck on June 19th, 1797, Boulton had already invested well over £11000 of his own money, which according to the Bank of England's inflation calculator, equates to £1,822,880 ($2,357,074) today. That number is a mere drop in the bucket if the work of Cule (1935) is correct, which details debts that well exceeded over £50000. Boulton was strapped for cash. Even though his reputation and financial well-being were precariously balanced upon the tip of a pinhead, Boulton remained steadfast in his dedication to the cause. By all accounts, he was a brilliant man who could transform otherwise perilous situations into grand opportunities. Of course, this is not to say that he did not make a few considerable mistakes along the way. Perhaps the costliest of which, as it relates to the Soho Mint, was the employment of the engraver Jean Pierre Droz. In Boulton's mind, an English coinage contract was all but inevitable, and as such, he needed to be prepared to answer the call at any given minute. This mixture of urgency bordering on panic is blatant in Boulton's communication leading up to the coinage contract in 1797 (Doty, 1998). His anxiety seems reasonable given that he had incurred great expense to build his Mint and the only possibility for him to recoup his money would be the securement of large coinage contracts. His financial difficulties were only one piece of his rather complicated problem. Boulton still needed to perfect his machinery, and even with that done, many more issues would remain.

NEWSPAPER CLIPPING CIRCA 1790 |

It is easy to get lost in the technical components of the Soho Mint as the process of applying steam power to the minting of coins was truly revolutionary at the time. One might even argue that this component was the most critical part for Boulton to perfect, and to some extent, that is true. However, even with the best technology, Boulton would have little hope of securing a coinage contract if he lacked the subsequent talent needed to engrave dies. Although Boulton had his fair share of technical difficulties, perhaps the next most significant threat to the early success of the Soho Mint was the constant struggle to secure the employment of talented engravers (Doty, 1998; Gould, 1970; Tungate, 2020). Like all other matters related to the early days of the Soho Mint, Boulton's ability to retain engravers teetered between his ability to pay them and what little work he had for them to do. After all, Boulton was strapped for cash, and providing a full salary to an engraver who was otherwise unengaged in work would only further his financial woes. This conflict between Boulton's need to employ talented engravers and the stark reality of his finances became all the more apparent in October of 1789. This is when Jean Pierre Droz reluctantly decided to relocate to Birmingham from Paris to fulfill Boulton's request in May of 1788 (Doty, 1998). Now responsible for Droz's full salary, Boulton found himself in a situation where he finally secured the talent but had nothing for him to work on and thus had no way of recouping his money. Without a large coinage contract in hand, Boulton seized any potentially profitable opportunity to find work for his engravers. Producing medals was one such opportunity. For instance, the medals struck in the early months of April 1789 provided something for the otherwise idle Droz to work on and generated a much-needed stream of revenue for Boulton (Pollard, 1968; Gould, 1970; Doty, 1998) 1.

Producing medals served other purposes beyond the generation of profit and work for engravers. After all, most medal orders were relatively small; thus, fewer dies needed to be engraved (Doty, 1998; Tungate, 2020). These small orders often did not generate enough money to justify the larger expense of developing the Soho Mint, so profit and work for engravers could not have been the only motivating factors. Given that Boulton was pioneering a new era of minting, his employees were understandably very inexperienced. Any work that Boulton could secure would provide valuable hands-on experience that would no doubt translate to innovation. The hope was that this innovation would pave the way for a smoother transition to mass coinage production. In other words, there were a lot of kinks that needed to be worked out, and it would be difficult to identify and subsequently solve those issues without a bit of trial and error. Although this point is well made, it strips the humanity of Boulton's general disposition for his employees and overlooks another likely motivator. From contemporary accounts, even from his rivals, Boulton is regarded as a true gentleman of the enlightenment. His ideas were well ahead of his time, and he adamantly fought on behalf of the common people whenever the opportunity presented itself. One needs to look no further than the Soho Manufactory to see his dedication to the working class. By the time the Soho Mint became more than a fleeting idea, the Soho Manufactory was bustling with activity engaged in any number of Boulton's business ventures (Robinson, 1963; Gould, 1970; Doty, 1998; Tungate, 2020). You see, Boulton was a manufacturer of England's finest luxury items. Among other things, Boulton would produce some of the finest coins, medals, tokens, clocks, and silver household accessories produced during the 18th century (Robinson, 1963; Mason, 2009; Loggie, 2011). These wares were enjoyed by some of the world's most prominent figures, including royal and noble families across the globe.

The sheer magnitude of Boulton's enterprise, paired with the utmost attention to quality, necessitated the employment of hundreds of men, women, and teenagers (Robinson, 1963, Doty, 1998; Tungate, 2020). One can only imagine how busy a typical day must have been for Boulton, given his involvement with even the most minute details of each venture. Despite being so busy, contemporary records indicate that Boulton took a personal interest in the lives of his workers and did what he could to make sure they were provided for. One such account details the general practice of Boulton hiring medical professionals, occasionally at his own expense, to look after his workers (Tungate, 2020). Eventually, Boulton would establish a deeply subsidized insurance program for his employees, which was far from the standard practice at the time. By all accounts, Boulton was a good boss, and this encouraged a lot of goodwill between him and his employees, which often translated to unwavering loyalty. This familiarity between Boulton and his employees often made it difficult for him to dismiss them when it was no longer viable to continue their employment (Doty, 1998). On occasion, the Soho Mint was idle with no large contracts to complete, and by no fault of their own, the workers had nothing to do. In these instances, Boulton went into debt, continuing to pay their salaries. Producing medals provided a source of relief. Although these commissions often did not generate large orders and thus revenue, they did provide much-needed experience, and more importantly, a financial justification for continued employment in times of stagnation.

So far, I have discussed the internal motivating factors for producing medals that primarily focus on Boulton's efforts to protect his employees, but it is crucial not to forget that Boulton was also a shrewd businessman (Doty, 1998; Robinson, 1963). At the time, coin collecting, which by extension the collecting of medals and tokens, was deemed the " hobby of Kings". Only those with sizable allowances would have the means to collect such luxury items, and not surprisingly, those with said funds were likely also to hold power and thus have influence (Gould, 1970, Tungate, 2020). By the time the Soho Mint was producing medals, Boulton had already established a reputation for quality that even King George III had admired. There is little doubt that he capitalized on this reputation to place medals and pattern coins in the collections of those with the most significant influence. His lobbying efforts for the coinage contract involved him gifting countless pattern pieces to influential members of the English Court in hopes of applying pressure on the privy council (Doty, 1998; Tungate, 2020). The medals were often far larger and more impressive than their smaller coinage counterparts and from contemporary records seemed to have made quite the impression. I can only imagine this further fanned the flames of Boulton's efforts to secure a coinage contract. In essence, the medals served as a form of advertisement for the Soho Mint which targeted the very people with the influence capable of swaying the privy council's decision. Producing high-quality medals and pattern coinage also likely resulted in residual effects for his other businesses, which in turn would generate more income for the cash strapped Boulton. To this extent, one cannot hope to fully appreciate the history of the Soho Mint without also considering the role medals played in its success.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Principles of design – "Simplistic Elegance"

Despite Boulton's reservations, the production of medals played an undeniably important role in the early formation of the Soho Mint. At the very least, their production helped to halt its financial collapse, provided work for its employees, and served as a powerful advertisement tool to further Boulton's lobbying efforts. In addition, the medals furthered Boulton's reputation as a man of the enlightenment and an icon of industrial ingenuity. This point is very clear in the high praise afforded to Boulton in contemporary writings. For instance, in 1801, Stebbing Shaw wrote the following about Boulton and the medals he produced at the Soho Mint in The History and Antiquities of Staffordshire:

" Various beautiful medals of our celebrated naval and other officers &c. have likewise been struck here from time to time by Mr. Boulton, for the purpose of employing and encouraging ingenious artists to revive that branch of sculpture, which had been upon the decline in this kingdom since the death of Symons in the reign of Charles II."

Even Boulton would eventually argue for the importance of medallic art in a letter to his lawyer dated September 8th, 1803 when he wrote, " Medalick art is less cultivated & encouraged in England than in any other European Nation; although the most durable record of Facts, & of the taste of times". This suggests that Boulton began to view the production of medals as more than a means to an end. Medals became a form of artistic expression that no doubt proved sufficiently challenging and thus intriguing for the ever innovating Boulton. In part, the design and production of medals were challenging because the stakes were far higher than that of coinage. At first, this might seem counterintuitive as large coinage contracts were the lifeblood of the Soho Mint, but the design and subsequent production of coinage were always somewhat limited by utility. This facet was removed for medals, and unlike the coins, the medals were primarily sought after by the rich and powerful, who often had very strong opinions of design. In numerous instances, a newly released medal by one of Boulton's competitors was harshly and publicly criticized by a person of power and influence (Gould, 1970). These instances could be very detrimental to the maker's reputation, and understandably this is something that Boulton would want to avoid at all costs. Furthermore, the very exclusive nature of medal production afforded greater competition for Boulton as there were already countless talented medalists in operation at the time. Almost no such competition existed for coinage, much less mass-produced coinage. In other words, those who would be interested in his medals would also likely be his most significant critics as they were already accustomed to relatively high-quality work.

|

The industrial revolution paired with the curtails of the enlightenment propagated several important changes across Europe. England was no exception to that rule, and with the establishment of the Royal Academy in 1768, society began further to appreciate the virtue of art and its practical utility. As noted by Loggie (2011), the appreciation of design and craftsmanship was no longer only enjoyed by the select elite but further propagated into what would be considered the middle-class (Gould, 1970, Tungate, 2020). The industrial revolution stimulated a greater appreciation for design and its practical implication to ordinary things, such as coinage. With design at the forefront of modern society, it was all the more critical that Boulton remain updated on the changing tastes of fashion and public opinion (Robinson, 1963, Tungate, 2020). This is all the more apparent when considering the medals and tokens of the French revolution. English public opinion was at first favorable of the French Revolution. However, as the events unfolded, public opinion changed drastically, and anyone still promoting the ideals of the French Revolution was likely to be harshly dismissed. Boulton had a contract to strike token coinage for the Monneron Brothers in 1791, which depicted several allegorical renditions of liberty in line with the ideals of the French Revolution (Margolis, 1988). In the changing tide of public opinion, these pieces had the potential to damage Boulton's reputation, and his response is apparent in the design and inscriptions of the medals he produced in 1793, depicting notable events of the French revolution (please see the Louis XVI Final Farewell medal for more details). This is only one of many examples in which Boulton's designs were altered to further align with public opinion and the ever-changing tastes of popular society.

Although events that unfolded on the international stage, such as the French revolution, are easily highlighted as influential in design, Boulton's dedication was far more profound. In the years leading up to the construction of the Soho Mint, Boulton became a renowned manufacturer of tasteful items, but in the process, he also became a consumer of similar goods (Robinson, 1963, Loggie, 2011). Boulton often requested that his connections across Europe send him items that were most popular in their region, which in turn kept him up to date on modern tastes (Robinson, 1963). He realized the importance of understanding who was likely to purchase his goods and directly catered to that audience's tastes. Again, the medals depicting the French Revolution are excellent examples of this, as the primary consumer of these pieces were English collectors. Boulton also became an avid consumer of relevant publications and, upon his death, had amassed a rather extensive library on the topics of art and design (Robinson, 1963; Loggie, 2011). There are numerous accounts of him pursuing these publications at length to understand better the nuances of regional differences in taste and design. He was also an avid accumulator of medals as he purchased entire collections of the works of several prominent artists such as Hedlinger and Andrieu (Gould, 1970). The term accumulator is carefully chosen as Boulton made it clear that he was not a collector in a letter dated February 5th, 1803.

" do not want to make a collection for the purposes of the historian or the antiquarian, nor to purchase Farthings at the expence of several Guineas, as I am not seized with the mania of a mere collector or antiquarian"

Although he detested being classified as a collector, as evidenced by the letter quoted above, he managed to amass an extensive collection of medals, tokens, and coins. In addition to these being study tools for his use, there is a good bit of contemporary evidence to suggest that he often loaned these pieces to his engravers to help perfect their craft (Gould, 1970; Pollard 1968; 1970). His sizeable social network also afforded him the opportunity to borrow items for study from some of the finest collections in the world, including those of royal and aristocrat families, which was all the more critical considering his rocky financial standing during the early years of the Soho mint. These practices became so extensive that Boulton essentially set up a museum within his home, where he could be free to study and interact with numerous priceless items at his leisure (Robinson, 1963, Loggie, 2011). Of course, he used this to his advantage when entertaining powerful and influential guests, which only further bolstered his reputation. As I mentioned before, Boulton was a shrewd businessman, and almost everything he did was to better perfect his craft. His dedication to quality and design were no exception.

BOARD OF AGRICULTURE MEDAL |

Through his studies, Boulton established a few basic principles of design that he employed throughout all of his business endeavors, including the production of medals. Contemporary society still valued classical art, but modern approaches were just as honored, and often the most popular pieces flirted the line between the two (Robinson, 1963, Loggie, 2011, Tungate, 2020). In general, Boulton aimed to accommodate both facets but did so by designing pieces that were simplistically elegant. His opinion is very well stated in a letter dated May 29th, 1794 to Charles Steven, " whether it be French, Roman, Athenian, Egyptian, Arabask, Etruscan or any other, simplicity of device is the greatest beauty of Money or medals". Boulton never sought to create overly elaborate designs as he thought doing so would detract from the main point of the piece. Gould (1970) argued that Boulton's reliance upon simple allegorical figures was a lesson learned from the art depicted on ancient coinage. Adopting simple yet elegant allegorical figures allowed for their reuse later with slight adjustments, which could reduce the overall cost of producing the dies needed to strike new items. Reusing old designs is well documented in the articles produced at the Soho mint, especially the coinage. Boulton's thoughts on allegorical figures are summarized in his letter to Droz dated December 12th, 1787, " Any allegorical figures should be few and simple and as free as possible from obscurity". This simplicity of design is well demonstrated on the numerous agricultural medals produced at the Soho Mint, including the (1793) Board of Agriculture medal and the 1789 medal commemorating the restoration of the King's health, both of which are depicted within this collection. Of course, customers suggested some designs that did not entirely adhere to the simplistic elegance Boulton strived to achieve. One such example is that of Davisson's Nile Medal. The design was sent to Boulton and the commissioner of the piece, Alexander Davisson, had a considerable say in the ultimate design (Pollard, 1970). In his 1970 publication, Pollard goes into detail about the numerous design changes requested by Davisson. In other instances, the final design of a medal was not unduly influenced by the customer but still violated Boulton's simple but elegant principle. Perhaps the best example of which is the medal commemorating the death of Gustavus III, the King of Sweden. Although the obverse design is in line with most other Soho medals, the reverse is rather intricate.

As the collecting of Soho wares became a fashionable symbol of social status, Boulton did his best to seize the opportunity (Doty, 1998; Tungate, 2020). By 1793 the Soho Mint was selling special proof sets of their products to collectors, including notable people such as King George III, Joseph & Sophia Banks, Richard Chippindall, Samuel Birchall, and Charles Pye, to name a few (Tungate, 2020). The production of these pieces had entered a new era, and Boulton was very keen on its possibilities. The production of these sets allowed Boulton to charge twelve times the normal rate for standard pieces, which generated more profit and required less work to do so. It appears Boulton applied the same logic to medals as he began marketing them in a host of different metals (e.g., gold, silver, copper, bronzed copper, gilt copper, tin, and white metal). Doing so allowed Boulton to appease the tastes of the upper echelons of society while also capturing the business of the middle class. In other words, Boulton was marketing himself as a one-stop-shop for all, which is a lesson he learned from the toy trade over the last three decades (Robinson, 1963). With the increased consumption of his goods, it became even more important that design and fashion remain at the forefront of his endeavors. It was imperative that he get the design of each piece just right, otherwise, he may face almost immediate criticism by the very people he hoped to influence. Hoping to make good impressions, Boulton realized the necessity of quality in terms of design and practical execution. The issue, however, was that Boulton would continue to struggle to secure talented engravers to carry out those designs well into the height of the Soho Mints popularity. Being the ingenious businessman that he was, he soon devised a way to overcome this obstacle while still balancing the demands of his precarious financial situation.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Promoting good practices in the science and art of medal making

From contemporary documents, it is abundantly clear that Boulton realized the importance of design. Robinson (1963) noted that the ability to incorporate tasteful designs without unduly influencing the cost or utility of items was all the rage in society, and Boulton set his sights on achieving this very early on. One would need to look no further than his efforts in the toy trade, where he produced some of the most elegant and yet affordable trinkets at the time (e.g., buttons, buckles, ormolu, etc.). As noted above, the study of art and design propagated well beyond the social elite, and now an entirely new class of connoisseurs found themselves delighting in its consumption. This brought about a change in the conceptualization of design. Consumers began to separate the design into two distinct categories, art, and craftsmanship. As Loggie (2011) argued, art referred to the conception of a basic design while craftsmanship referred to the execution of the design into tangible artifacts. This reconceptualization gave rise to the rampant acceptance of drawing as a critical component essential to design. It allowed for a practical way to train craftsmen to execute designs. Within this social climate, those who supported these efforts were often held in very high esteem.

Boulton was among the many who endeavored to cultivate the arts in England. He undoubtedly did so to build his reputation, but it also stands to reason that doing so was an attempt to solve an issue that plagued the Soho Manufactory, and later the Soho Mint, a lack of talented engravers. All of Boulton's studying on design and the craft of its execution culminated by 1803 with the development of a set of step-wise procedures (Tungate, 2020).

" The first thing to be done is to express a good design in Words; the 2d is to make a good drawing of the Idea; the 3d is to make a correct model in wax w[hich] may be altered to ye taste of the committee; & the 4th is to engrave it in a steel die at Soho & lastly to strike ye medal in gold, silver, or copper in my improved press. "

STAFFORDSHIRE AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY TRIAL STRIKE |

Boulton’s instructions are drastically simplified to appeal to the ease with which his Soho Mint produced items, but in reality, there were several intermediary steps to take. For instance, once the main design was engraved in steel, the dies would typically be tested through a series of trial strikes. Remnants of these efforts are rare but still exist for collectors to enjoy today. The trial strike of the Staffordshire Agricultural Society medal pictured to the left is an excellent example. In this case, the trial strike included the main design but omitted other important details found on the actual medal (e.g., the laurel wreath is in her hand, the legend, and the engraver's initials). Although the third, fourth, and intermediary steps discussed above seem to have been standard practice at the time, the first and second are worthy of further discussion. The first step dictates the need to express a good design in words before any drawing or modeling begins. This step often seems to have been absent among his contemporaries and is something that Boulton likely drew upon as a way to insert his influence on the design of a medal before any real work began. This makes sense given the relatively high stakes involved, both from the potential of social rejection and the delicate balance of his finances. This extra step also afforded yet another layer of practice to help his designers improve their skills. Making a good drawing of the idea is at the core of the practices instilled very early on at the Soho Manufactory and later at the Soho Mint. As noted by Loggie (2011), drawing was seen as a core component of executing tasteful designs, but unlike creating the actual designs, it was thought that any motivated and reasonably skilled person could be trained in the mechanical art of drawing. The idea being that teaching someone how to draw would translate into better skills at executing the designs provided, and thus completing the circle applying the genius of design with the practical utility of everyday items (Loggie, 2011; Tungate, 2020). Boulton appears to have endorsed this idea early on as he eventually set up an industrial design school at the Soho Manufactory, employing as he described " young countrymen of ability" to draw. These young men were often retained under contract for multiple years with the hope of exploiting their progress in the form of new designs for the numerous wares he produced (Loggie, 2011). From this contemporary document, we learn that it was not uncommon for Boulton to send his best students to events such as operas on his dime in hopes of further cultivating their talents. The goal as described by Boulton was to " establish a school of designers who should give to the Soho Factory an artistic style and finish not obtainable elsewhere". Boulton's vision was simple in nature but difficult to assemble, especially in the early days of the Soho mint when money was scarce.

Boulton's industrial design school was a success by most standards, as some of the most notable die engravers in English history were apprenticed under his direction at one point or another (Tungate, 2020). At least three members of the Wyon family trained at Soho, including Peter, the father of William Wyon, who would go on to engrave the Una Lion design that has been so prevalent in recent auctions. Other notable engravers include John Gregory Handcock, Edward Thomason, and Thomas Halliday, and John Phillps. More specific to the Soho Mint, Boulton had applied the principles of his industrial design school to setup a network of apprenticeships for promising young boys and girls. More often, these apprentices came from low-income backgrounds and Boulton took care to provide them housing, food, and a small stipend for their work at Soho. Doing so was often very costly, but it typically produced into loyal and skilled employees which were highly valued by Boulton. An excellent example of this is John Phillp, who eventually become the assistant designer at the Soho Mint (Tungate, 2013).

Although Boulton was indeed a gifted technical drawer, as evident in his numerous sketches, he was far removed from providing the needed instruction to his students. After all, Boulton was neither an artist nor an engraver. Luckily for him, he had a vast network of very talented artists to assist in his efforts. These individuals would serve as consultants to his students and, on numerous occasions, served as a source of guidance on the coins, tokens, and medals produced at the Soho mint. This was especially true when the subject of the medal was particularity sensitive, as was often the case when depicting a reigning monarch on a medal. For instance, when designing the medal commemorating the marriage of the Prince of Wales, Küchler was instructed to consult none other than the official painter to the prince, Richard Cosway (Pollard, 1970; Tungate, 2020). Another notable consultant that helped Boulton with a number of projects was, Benjamin West, the President of the Royal Academy. These consultants undoubtedly played a large part in helping the Soho Mint create the numerous pieces of medallic art that are still celebrated over two centuries later by modern collectors. Eventually, both now and then, the Soho Mint would become synonymous with high-quality medals of the utmost taste both in terms of execution and design. This reputation is undoubtedly the byproduct of Boulton's efforts to cultivate gifted designers and craftsman at Soho.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Notable engravers

In the process of establishing the Soho mint and building the immaculate reputation that it eventually enjoyed, Matthew Boulton would go on to employ some of the most talented engravers of the era. Although this section is far from exhaustive, the goal is to briefly introduce the engravers who had the most influence on the Soho Mint. To do so, I have compiled a list using the work of Tungate (2020) as a reference to identify the engravers who were most prolific or contextually important. It should be no surprise that Jean-Pierre Droz and Conrad Heinrich Küchler are at the very top of the list. It can often be difficult to fully understand the scope of their influence as, over the years, many pieces were considered but not produced. As such, this section only focuses on the medals that were actually struck the Soho Mint. I will do my best to refrain from discussing any influence upon token or coin designs with the hope of incorporating that information elsewhere at a later date. Some of the information contained here, as it relates to both Droz and Küchler, is repeated in my other registry set titled " What comes next? You've been freed. Do you know how hard it is to lead?", but a good bit of new information is also presented. The information about Rambert Dumarest, Noel-Alexandre Ponthon, and John Phillp is entirely new. Although the medals are rather impressive, I have decided to forgo any discussion of them here to provide more detailed information in the listing for each piece.

Jean-Pierre Droz

As already noted, the early years of the Soho Mint were fraught with difficulties. Beyond the technical constraints, Boulton had a severe issue recruiting talented engravers. At first glance, Droz seemed to have the solution to several of the issues. By most accounts, Droz was a very talented engraver, but he also possessed a solid technical savviness that further impressed Boulton. The two first met in December of 1798 when Boulton, Watt, and Thomas Jefferson visited Droz in Paris to see a demonstration of his latest invention (Pollard, 1968; Doty, 1998). While demonstrating his new technique, Droz argued that he had made significant improvements to the presses and the process of multiplying dies. Boulton being deeply involved with the button trade and his experiences with the Sumatra coinage produced earlier made him keenly aware of the difficulty of producing a sufficient number of dies to complete a large contract. It seems likely that Boulton viewed Droz as a solution to his technical issues (e.g., the multiplication of dies and the improvement of presses) and the issue of not having a reliable and talented engraver in his employ. The production of coins and medals differed from the button trade or even the Sumatra coinage because Boulton found himself without an engraver skilled enough to engrave a head upon a die. Doing so would be vital should he ever hope to secure a regal coinage contract with England.

1789 GEORGE III RESTORED TO HEALTH MEDAL |

Boulton, seemingly swept off his feet by the perceived abilities of Droz, offered him a position at the Soho Mint with a generous salary and the option to live rent and tax-free at Soho House (Pollard, 1968). In return, Droz had to produce dies for coins, tokens, and medals as needed and provide modeled designs for his improved coinage press (i.e., the sexpartite collar and the ejecting mechanism). As history would soon reveal, Boulton would ultimately be estranged from Droz, whom he at one point considered a friend. By June of 1790, the relationship between the two had deteriorated to the point that arbitration was required to settle their affairs. This led to a contract between the two signed in November of 1790 (Doty, 1998), which dictated several duties Droz must execute over two years. The new terms required Droz to complete the master dies for the pattern pieces, train workers to engrave the collar pieces, and produce the die-cutting lathe. Not surprisingly, he failed to complete any of these tasks (Pollard, 1968). After arbitration, Droz was eventually dismissed, marking the departure of one of Soho's most prominent villains. At a time so critical for Boulton's finances, the Droz mistake ended up costing him over £3000 with very little to show for it, which according to the Bank of England's inflation calculator equates to £462,560 ($630,936) today.

Although Droz's involvement would continue to be a source of agitation for Boulton for many years, some good did come out of it. Had Boulton secured a coinage contract with the English government at the onset of his involvement with Droz, it would have undoubtedly spelled disaster. As detailed in my other custom set, the Soho Mint was not prepared to strike any large coins with any quantity. The Monneron contract was difficult enough, which would pale in comparison to the giant twopence pieces that would be stuck in 1797. Although nothing more than a coincidence, as neither Boulton nor Droz were able to predict the future, in hindsight, the delays imparted by Droz may have ultimately saved the Soho Mint and Matthew Boulton from complete ruin. Modern researchers can appreciate this fact now, but I am sure Matthew Boulton viewed things through a very different lens. From a practical, contemporary standpoint, Droz produced several dies and subsequent specimens of his pattern halfpenny pieces, which Boulton used as advertisements to further his lobbying efforts (albeit this work hardly justified the expense). Of the five proposed medals, only two were produced, one of which cannot be conclusively determined to have been struck the Soho Mint. The arbitration process had resulted in Droz making copies of the molds produced during his tenure as the Soho Mint for his own use, one of which was the design for the George Agustus Eliott Medal commemorating the defense of Gibraltar. According to Pollard (1968), these medals appear to have been struck between 1816 and 1820, corresponding to a period well after Droz had departed Soho. As such, there is only one medal produced at Soho for which Droz deserves any credit – the 1789 medal produced to mark the King's restoration to health. More information about this medal can be found by viewing the individual item listing within this set.

There is little sense in disputing the artistic merits of Droz. From both contemporary and modern accounts, he is seen as one of the most gifted engravers of his time, but his tenure at the Soho Mint was marred by misfortune. We may never truly know the extent of the issues between Boulton and Droz, but as Pollard (1968) argued, his time at Soho was a dark stain on an otherwise prosperous career. Regardless of the events that transpired, modern collectors have a series of interesting coins, tokens, and at least one medal to pursue, thanks to the relationship between Boulton and Droz.

Rambert Dumarest

Although, in my opinion, the work of Dumarest is on par with that of Droz or Küchler, he has yet to garner the same level of attention and thus not nearly as much information about him is readily available. According to Forrer (1904), he was born in Saint-Êtienne in September of 1760 (it is worth noting that the source reports 1860, which is invariably a typo as he passed away in April of 1806). As a gifted engraver, he quickly found work at the Manufacture d'armes de Saint- Êtienne, engraving sword hilts, among other articles. In desperate need of a talented engraver, Boulton initially offered Dumarest a position at Soho during the arbitration process with Droz. Remember, Boulton was in a constant state of anticipation that a large government coinage contract would be granted. With the removal of Droz, he was left without a single talented engraver. According to Doty (1998), Dumarest did not immediately respond, which was in part a deciding factor that led Boulton to extend a new contract to Droz for an additional two years. Dumarest eventually accepted Boulton's offer and arrived at Soho on August 8th, 1790, which by coincidence was the day marked to celebrate Matthew Robinson Boulton's twenty-first birthday (Margolis, 1988). A complete account of this event is detailed in a newspaper clipping found just below the illustration of Matthew Boulton at the beginning of this set. 1791 JEAN JACQUES ROUSSEAU |

Dumarest was a prolific engraver at the Soho Mint but is only credited with producing four medals during his tenure. Of those four, only two of which can indeed be considered his own, both were struck by order of the Monneron brothers for sale in France. Of course, these two pieces were the medals depicting Marquis de Lafayette and Jean Jacques Rousseau, and both struck in 1792. An example of each is contained within this set that were once part of the Boulton family collection. The Rousseau piece (pictured above) has retained its original silver-lined brass shells. The reverse of the Peace of Amiens and Boulton's Medallic Scale medal are often attributed to him, but it appears some debate remains on the validity of these claims. As such, only two medals can truly be attributed to him without controversy. However, it is worth noting that Noel-Alexandre Ponthon engraved the reverse of both the Lafayette and Rousseau medals. Most of the work completed by Dumarest can be found on the numerous tokens struck at the Soho Mint, such as the infamous Glasgow Halfpenny token depicting Clay, the river god. Despite being a very talented engraver, Dumarest evidently lacked confidence in his ability, which was partially driven by his perfectionist disposition (Doty, 1998). I am sure the chaotic nature of the early days at the Soho Mint did little to calm his already heightened nerves. Dumarest eventually grew tired of England and returned to Paris in the Spring of 1791. Although his tenure at Soho was very short, his employment was rather lucrative for him as he was paid at least £137 for the work he completed (Tungate, 2013). He would go on to be a celebrated craftsman of fine jewelry and won the grand prize in the 1795 medal competition for his depiction of Rousseau on the medal struck at the Soho Mint. His status would be elevated further in 1800 when he was elected a member of the National Institute of Science and the Arts. Although his tenure at the Soho Mint was relatively short, he produced numerous celebrated medals and tokens. One cannot help but wonder what he might have accomplished had he stayed under the employ of Boulton.

Noel-Alexandre Ponthon

With Dumarest growing homesick it became clear that would need to find a replacement and quick. So far, Boulton had already employed two French engravers so it should not be terribly surprising that he would seek a third. Boulton’s Paris agent, Dr. Swediaur, highly recommended and subsequently hired on behalf of Boulton a very talented engraver in his mid-20s named Noel-Alexandre Ponthon (Margolis, 1988). This arrangement was first settled on June 16th, with the intention that Ponthon would begin work at the Soho Mint in July, but he was delayed several weeks and did not arrive in Birmingham until August (Doty). This delayed necessitated the prolonged employment of Dumarest, who by all accounts seems to have been absolutely miserable having to endure the bleak prospects of a life in England. As we know, Dumarest would come out no worse for the ware Ponthon would take over his responsibilities with seamless perfection. His terms of employment provided him with an annual salary of £80 with the expectation that he would engrave dies for coins, tokens, and medals for the Soho Mint. As was often the case, Ponthon also did engraving work others while in Birmingham to further supplement his income. Like his predecessor, Ponthon’s most notable work appears on several very popular coins and tokens. For instance, he engraved the reverse designs for the 1794 Madras coinage, and the 1793 Leeds Halfpenny Token, and the 1794 Daniel Eccleston Halfpenny Token, and reverse of the 1793 Bermuda Penny. As already noted, he engraved the reverse dies for the Rousseau and Lafayette medals struck in 1791, as well as the reverse dies for two Frogmore medals struck in 1795, one celebrating Queen Charlotte’s birthday, and the other denoting the visit of the Prince of Wales to Frogmore. Like his other French counterparts that came before him, Ponthon’s employment at the Soho Mint was relatively short. He would eventually leave the Soho Mint in September of 1795, but luckily for Boulton by this time he had already secured the employment the most prevalent engraver to work at the Soho Mint, Conrad Heinrich Küchler (Doty, 1998).

John Phillp

As one of the more distinguished graduates of Boulton's apprentice program, Phillp would go on to engrave many dies at the Soho Mint. By the midsummer of 1800, his seven-year apprenticeship came to an end, and he quickly found work in London while also continuing to fulfill requests made by Boulton. Having arrived in the early part of 1793, John Phillp's tenure at Soho closely overlapped with that of Conrad Heinrich Küchler (Doty, 1998; Tungate, 2013). It appears the two worked very closely on several projects, one of which indicates that Küchler might not have been particularly fond of Phillp. Nonetheless, Phillp was a talented engraver, and Boulton thought enough of his talents to retain him at Soho as the assistant designer under Küchler. This became particularly useful as Küchler become increasingly busy with the eventual success of the Soho Mint, and as he continued to age and his work speed began to slow. Phillps would go on to take over an increasing number of Küchler's projects.

GOLD WESTMINSTER FIRE OFFICE MEDAL |

Learning from his prior mistakes with Droz, a contract was established between Boulton and Phillp. We know that he was compensated £48 annually but often received other payments for extra work that Boulton considered above and beyond his normal obligations (Tungate, 2013). From the 1850 catalog sale of the Soho Mint it is clear that Phillp was considered one of the best engravers employed by Boulton. The front cover of the auction catalog lists for sale a series of dies for both coins and medals that were " most beautifully executed, principally by the celebrated Küchler, and by Droz and Phillp”. His place in Soho history is well ingrained due to his merits as an artist, but unfortunately, his name is also tied to a conspiracy that seems to have developed over a century after his death. Dickinson (1936) suggests without further evidence that Phillp is the illegitimate child of Boulton, which is a rumor that is seemingly still alive today. Doty (1998) noted that there is no evidence, either contemporary or modern, to suggest this is the case. Although the two men do coincidently look similar, that is hardly enough to support the claims made by Dickinson. Furthermore, this claim directly contradicts the profile of Boulton provided by his contemporaries and reiterated by Dickinson. If it were true, Boulton's indiscretion would have undoubtedly been seen as a stain on his impeccable reputation as the "Princely Boulton" so aptly described by Dickinson. As such, it seems highly unlikely that there is any truth to the controversy, but nonetheless, it adds a layer of mystery for those interested. It is also worth noting that his name, although correctly spelled Phillp is erroneously reported as Phillip, Phillips, and Philips throughout several publications. I admit that the spelling was a point of confusion for me as well until I was able to view contemporary documentation. This fact is further complicated by the numerous signatures he used to denote his work, I.P., ? · ?, and PHILLPS are the most notable (Forrer, 1909). During his employment at the Soho Mint, he engraved dies for a total of six medals. The Westminster Fire office, Hafod Friendly Society, and the St. Albans Female Friendly Society medals are completely his original work. He also collaborated with both Küchler and Pidgeon on several medals, tokens, and coins.

Conrad Heinrich Küchler

The majority of the information I will present in this section can be traced back to Pollard (1970). In his article, Pollard reproduced a fair amount of the correspondence between Boulton and Küchler, and it is this material that has proven so invaluable to the topic at hand. Küchler's role in Soho history began in the early part of 1793, and during his 17-year career under the employment of Boulton, he produced a total of 33 medals. In a letter dated March 13th, 1793, Boulton sets the terms of Küchler's employment, which provides a glimpse into how Boulton approached the medal business. In this letter, Boulton gives Küchler the option of being paid per die produced or an even portion of the profit gained from the sale of each medal Küchler engraved. Küchler agreed to the former, and he remained in London for two more years, engraving several dies for Boulton. How Küchler is compensated highlights Boulton's early disregard for producing medals relative to his efforts to gain coinage contracts. Although his offer to Küchler is generous, it pales compared to the concessions Boulton made to bring Droz on board. It nearly seems as if Boulton secured the help of Küchler for no other reason than to have a second skilled engraver should anything happen to Ponthon.

It seems so uncharacteristic of the overly ambitious Matthew Boulton to essentially look down on the opportunity to produce yet another exceptional Soho product, but as modern enthusiasts, we already know why. As a recap, Boulton had endured great expense to build his Mint, pay his employees (think of all the money he spent appeasing Droz), and secure material for an English coinage contract that he was convinced was right around the corner. Boulton felt the financial weight of operating a mint that was yet to produce a coinage contract that allowed him to recoup the money he invested (Selgin, 2003). This could, in part, explain the terms Boulton offered to Küchler. Both options would ensure that Küchler had to produce something to get paid, which is a painful lesson he learned from Droz. The second option would have further reduced Boulton's financial burden by offsetting both men's initial production costs. Either way, the options presented to Küchler were likely due to Boulton's financial hardships at the time. The excerpts from the archived correspondence between Küchler and Boulton provided by Pollard (1970) support this notion. In the summer of 1795, Küchler moved to Birmingham and continued to work for Boulton while still petitioning for the money owed to him. This seems to escalate in a letter by Küchler dated January 21st, 1796, which details his work and the amount he has been paid. On this date, Küchler had completed over £250 worth of work but had barely received over £130 in compensation. The debt was eventually addressed, but it appears this was a reoccurring pattern that eventually changed how Küchler was compensated for his work. 1800 GEORGE III PRESERVED FROM ASSASSINATION |

Shortly after, the terms of Küchler's employment were slightly altered in a way that seems to benefit both parties mutually. According to Pollard (1970), the new terms still afforded Küchler payment for each die he engraved, but they also provided a portion of the profits from selling specific medals. These terms, of course, came with some caveats. First, it distinguished between medals that were commissioned to be struck by but not sold by the Soho Mint (i.e., private accounts) and medals that were struck and subsequently sold by the Soho Mint (i.e., joint accounts). Under the new terms, Küchler would be compensated for the dies he produced for both classifications, but he would also be granted a portion of the profits for the latter category. Second, the portion of profits was not guaranteed until the total expense of production was paid for. Under the new terms, Küchler could end up owing Boulton money if the sales for the joint accounts were lackluster. The excerpt provided by Pollard (1970) provides a contemporary example of how this would work. This is an important fact to note because it underscores Boulton's desire to protect himself, the Soho Mint, and Küchler.

Although Boulton was a generous man, he was also in the business to make money (no pun intended), so it makes sense that he would want to protect himself as much as possible. The new terms afforded him to do so but also allowed him to remain generous with Küchler should their work be successful. The new terms suggest that perhaps the business of striking and selling medals was not as lucrative as Boulton would have liked. There is evidence to suggest that this may be the case, as many medals were in surplus at the Soho Mint up until its final demise in 1850. Over 300 medals appeared in the 1850 sale alone2, and at least another couple hundred were sold in 1912 from the Matthew Piers Watt Boulton collection. This, of course, also does not include the numerous pieces that were part of the James Watt Jr. Collection or the Boulton family holdings (independent of the M. P. W. Boulton collection). All of this suggests, generally speaking, that there was no shortage of supply when it came to several of the medals produced. This is even more obvious when considering that some of these medals come up for sale very frequently. For example, the 1793 Execution of Louis XVI "final farewell" medal has had over a dozen auction appearances this year alone. This is notable because it was the first medal that Küchler produced for the Soho Mint (Pollard, 1970). The fact that Küchler renegotiated his terms of employment to a salaried position after a brief leave of absence in 1802 further suggests that the business of producing medals was not the most lucrative. Despite not generating the large sums of money needed, the medals did provide experience for Boulton's workers and, as already discussed, played a pivotal role in the eventual success of the Soho Mint.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Conclusion

The fact that the medals produced at the Soho Mint played an essential part in its history and, to some extent, its success is undeniable. From a practical standpoint, the medals generated much-needed profit for an otherwise cash-strapped operation and provided much-needed experience for the employees of the Soho Mint. In addition, producing medals provided opportunities to further Boulton's efforts to recruit talented engravers and justified the continued employment of skilled laborers at the Soho Mint in times of stagnation. From a social-political standpoint, the medals served as an advertisement that was most likely to be consumed by the very people who had the power and influence to win the favor of the privy council. For example, from contemporary accounts, we know that the medal celebrating the King's recovery engraved by Droz left a lasting impression on those who acquired it, many of which were Lords of the committee on coin. It stands to reason that this strong impression helped keep other competitors at bay, which increased Boulton's chances of securing a contract to strike regal copper coinage. Beyond these factors, I imagine the craftsmanship so boldly displayed on these pieces served to bolster Matthew Boulton's reputation of providing nothing short of the best (Tungate, 2010). Boulton's reputation built over decades in the toy trade seems to have been even further elevated by his development and subsequent devotion to the Soho Mint. In my opinion, this point is best summarized in the September 5th edition of The Penny Magazine published in 1835. One of the main articles details the development of Soho, the area about two miles outside of Birmingham from a hearth of empty land to a bustling industrial center. Only a tiny portion of the article details the Soho Mint, but it provides a very brief holistic view of Matthew Boulton and all of the business endeavors he engaged with. In summary of these facets, the author provided the following as their conclusion:

" It would be doing injustice to this great theatre of practical art, and to the able and large-minded man by whom its glory is owing, if we separately considered the various improvements which have issued from thence, or regarded only their personal effects as to Mr. Boulton and his partners. Soho, although a nominally private concern, has, in point of fact, been an establishment of the very highest national importance; and this not only in its large operation upon the commercial interests of the nation, in extending the power of man, and in enlarging the comforts and conveniences of life, but also in improving, in a degree beyond calculation, the public mind by encouragement it has given to artists of all descriptions, and still more by the healthy rivalry and competition in skill which is kept continually in exercise."

Matthew Boulton, and by extension, the Soho Mint, left a lasting impact that appealed to almost all facets of contemporary society. Forgoing any discussion of the coinage, the production of medals helped facilitate the encouragement of practical art, which was at the height of popular culture at the time. Although not immediately apparent, the societal climate of the time was ripe with a push towards English independence from imports, mainly that of France, which had long been considered the world's design capital (Loggie, 2011). The efforts on behalf of Boulton to encourage better design both at the Soho Mint and the Soho Foundry at large could in some form be considered a patriotic act. No matter how you choose to look at it, the fact that the medals played an integral part in the history of the Soho Mint is undeniable.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Footnotes

1. It is worth noting that medals were not the only items used to keep engravers busy during the early period of the Soho Mint, as several tokens were also struck.

2. Decent quantities of medals were struck just prior to the auction in order to offer mostly complete collections of Soho medals. There is no clear distinction made in the auction catalog between early and late striking (Vice, 1995)

References

Cule, J. E. (1935). The Financial History of Matthew Boulton 1759-1800. (Master's Thesis). Retrieved from University of Birmingham Research Archive.

Doty, R. (1998). The Soho Mint and the Industrialisation of Money. London: National Museum of American History Smithsonian Institution.

Frey A. R., & Salton M. M. (1973). Dictionary of Numismatic Names with Glossary of Numismatic Terms. London: Spink & Sons Ltd. And Organisation of International Numismatists.

Forrer L. (1904) Biographical Dictionary of Medallists (Vol. 1). London: Spink & Sons Ltd.

Forrer L. (1909) Biographical Dictionary of Medallists (Vol. 4). London: Spink & Sons Ltd.

Gould, B (1970). Mottoes and Some Designs for Boulton's Medals. Seaby's Coin & Medal Bulletin, November, 396-402.

Jones, M. (1989). Medals of the French Revolution. The Royal Society of Arts Journal, 137(5398), 640-646.

Robinson, E. (1963). Eighteenth-century commerce and fashion: Matthew Boulton's marketing techniques. The Economic History Review, 16(1), 39-60.

Loggie, V. A. (2011). Soho Depicted: Prints, Drawings and Watercolours of Matthew Boulton, His Manufactory and Estate, 1760-1809 (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I.

Margolis, R. (1988). Matthew Boulton' s French ventures of 1791 and 1792; tokens for the Monneron Frères of Paris and Isle de France. British Numismatic Journal, 58, 102-112.

Mason, S. (2009). Matthew Boulton selling all the world desires. London and New Haven: Yale University Press.

Pollard, J. G. (1970). Matthew Boulton and Conrad Heinrich Küchler. The Numismatic Chronicle, 10, 259-318.

Pollard, J. G. (1968). Matthew Boulton and J.-P. Droz. The Numismatic Chronicle, 8, 241-265.

Tungate, S. (2013). Workers at the Soho Mint (1788-1809). In K. Quickenden, S. Baggott, and M. Dick (Eds.), Matthew Boulton (pp. 179-197). Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Company.

Vice, D. (1995). A fresh insight into Soho Mint restrikes & those responsible for their manufacture. Format Coins, Birmingham, 3-14.

Set Goals

This set is a tribute to my friend, Bill McKivor, who recently passed away. Although we only knew each other for a relatively short time, Bill quickly became one of my favorite people. He is the sole reason I ended up collecting the medals of the Soho Mint, and as such, it seems fitting that his memory lives on in my collection. Bill had an eye for exceptional quality, and although he handled most of the Boulton Family collection, the medals held a special place in his heart. I, too, have developed a keen fondness for the Soho medals, and so far, I have been successful in locating many examples paired with silver-lined brass shells. Several of them once resided in either the Boulton family or the James Watt Jr. collections. This set aims to build a top-notch collection of Soho medals, emphasizing the ones Bill held in such high regard. The pieces that comprise this collection have been carefully selected. When appropriate, I have included the relevant provenance for each piece and the historical significance of the event or person depicted on the medal.

As of April of 2024, I have over three dozen additional medals to add to this set. Some are already graded, but the bulk of them are raw. Once I have more time and funds these pieces will be graded and slowly added to the set as I take the time to enjoy their relative history.

| | | | | | |

| | | | | | |

|

View Coin

| 1791 France New Constitution "Serment Du Roi" Medal (Maz-244)- (Lettered Edge) |

FRANCE - ESSAIS

|

BRONZE 1791-DATED MAZ-244 NEW CONSTITUTION

|

NGC MS 64 BN PL

|

This is an incredibly cool and attainable medal struck at the Soho Mint to commemorate an event that transpired during the French Revolution. The Monneron brothers initially had the idea to strike a series of medals to commemorate exceptional events and figures in French history, but the series was abruptly abandoned due to the financial failure of their ventures. Only three medals were produced out of the proposed series. The current piece, often dubbed the “Serment Du Rois ‘Je Jure’ medal was struck to immortalize the King’s acceptance of the new French Constitution. It is interesting to note that Dupre opted to provide the date of the commemorated event on the medal as opposed to when it was struck (i.e., 1791 instead of 1792), which seems to have been a general practice at the time (Tungate, 2020). This is one of the few medals in this collection that allows seeing an engraver’s work that is not overtly detailed in the main write-up. Despite his comparatively limited involvement with the medals struck at the Soho Mint, Dupre was an extraordinarily talented artist.

The pictures are courtesy of NGC's new PhotoVision Plus Service.

Historical Context: The French Revolution has captivated the interest of countless historians, which has generated an abundance of modern interpretations. Those interested have no doubt had the opportunity to read these works but may not have had a chance to read an unaltered contemporary account of the series of events that transpired. To this end, I present a series of publications from 1791 that provide a glimpse of contemporary analysis from the British perspective. I hope that readers will consider this information in conjunction with the write-ups for other relevant medals in this set.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Derby Mercury

Thursday, August 18 1791

FRENCH CONSTITUTION.

The Form of Government which the French nation has adopted, having met with applause from some, and the highest disapprobation from others, it appears necessary, since it is now finished, to present to the public a few of its fundamental principles: - First, the basis of the whole form is supposed to be, that every citizen shall enjoy protection and encouragement in every part of his inoffensive conduct, civil and religious. To secure this, the National Assembly has endeavored to provide for a constant free Representation of the People, to be called the Legislative National Assembly, from whom the laws are to proceed: with such a legislature they suppose the laws will be pure and impartial. -to ensure the faithful administration of these laws, they have thought it necessary to restrict the King to the execution of them only, without having an influence in their formation, by his Ministers or other dependents. To him is given the care and government of the Kingdom call one he is to provide for its internal and external safety, and to see that justice and support be given to the citizens alike period to encourage him in this arduous, yet illustrious and benevolent engagement, the Nation has allowed him dignity and emolument, as the head and organ of a great nation. The People, the Legislature and the King are subject to public Laws, of which each are supposed to approve: the authority of the King is plainly defined; the extent of the decrees of the Assembly is fixed; the rights and duties of the citizens declared. Thus the Legislative National Assembly, which is deemed the voice of the People, makes the laws; - the King sanctions and puts them in force - and the People reverence and obey the Law, considering it as the will of the nation, and respect the Chief Magistrate, as their Head and Organ.

The above may be called the foundation of the New Constitution; from which, in the following Abridgement, are readers may form a tolerable idea of the whole fabric: -

On the 5th instant, M. Thouret, in the name of the Committees of Constitution and Revision, presented from them to the National Assembly the report, intituled, The French Constitution; and M. Fayette moved, that a decree should be prepared for presenting the Constitutional Act to the most independent examination and free acceptation of the King.

After the preamble, and seventeen Articles of the Declaration of the Rights of a Man and a Citizen, it precedes thus: “the National Assembly, meaning to establish the French Constitution on the principles recognized and declared before, abolishes he revocable by, the institutions that injure liberty and equality of rights. - there is no longer Nobility, or Peerage, or distinction of orders, or feudal system, or patrimonial jurisdictions, or any of the titles, denominations, and prerogatives derived from them, or any orders of chivalry, corporations or decorations, for which proofs of nobility are required, or any other superiority, but that of public officers and the exercise of their functions. - no public office is any longer saleable or hereditary. - there is no longer, for any part of the nation, or for any individual, any privilege or exception to the common right of all Frenchmen. - There is no longer warden ships, or corporations of professions, arts and craft.- The law no longer recognizes religious vows or any other engagement contrary to natural rights, or to the Constitution.”

This report is then classed under separate heads. - Under the first, it declares that the Constitution guarantees as natural and civil rights, that all citizens are admissible to places & employments within any distinctions; that all contribution shall be divided equally among the citizens, in proportion to their means; that the same crime shall be subject to the same punishments without distinction of persons; liberty to all men of going, staying, or departing; of speaking, writing, and printing their thoughts, and of exercising the religious worship to which they are attached; liberty to all citizens of assembling peaceably, and of addressing to all constituted authority, petitions individually signed; and it declares there shall be a general establishment of public succours for the relief and instruction of the poor. Under the 2d head, it declares the Kingdom shall be divided into 83 departments, the departments into districts, and the districts into cantons; it settles the election of municipal officers, declares who shall be French citizens, and who shall be deprived of that privilege (by naturalization in a foreign country, consumacy to the laws, an initiation in any foreign order which requires proofs Nobility). Head the 3d relates to the public powers; it declares the French Government Monarchial, and the constitution representative; the executive power is the King's; - the legislative, the National Assembly’s; the representative shall be 745; the electors to consist of every active citizen not under 25 years of age, who has resided one year in the Canton for which he votes, and who is not a menial servant; every citizen is eligible as a representative who is not a Minister, were employed in certain places of the Household of Treasury. - the representatives are to meet the 1st of may; but shall perform no legislative act tell their number be more than 373. The National Assembly shall be formed by new elections every two years.

The other parts of the3d head relate to the Royalty, Regency, and King. The royalty is declared indivisible, hereditary to the race upon the throne from male to male, to utter the exclusion of women. The King's title shall be only King of the French, and his person sacred and inviolable. On his accession he shall take an oath, “to employ all the power delegated to him to maintain the constitution decreed by the National Assembly, in 1789, 1790, and 1791, and to cause the laws to be executed.” If he violates this oath, leaves the Kingdom, heads an army against the country, or does not oppose such a one, he shall be held to have abdicated the throne. The King is to be held in minor until the age of eighteen, his next relation (aged 25) not a woman, is in such case to be Regent, and to take an oath similar to the King’s; he is, however, to have no power over the person of the King, the care of whom shall be confided to his mother. In case of mental incapacity, there is also to be a Regency. The presumptive air is to bear the name of Prince Royal, and cannot leave the Kingdom without the King’s and the Assembly’s leave; the Minsters are to be chosen by the King, but cannot be sheltered by him from responsibility.