Set

Category:

World Coins

Set Name:

Dineros of Peru and their Antecedents

Set Description:

Introduction To My Set

This set is meant as an informative showcase for Peruvian Dineros and those denominations leading towards the Dinero. Peruvian minors are a largely neglected sub-grouping of numismatics, with minimal literature dedicated to their study. I hope the research I have done for this set goes some way to rectify the paucity of information on the Dinero series. On the front page you will find a complete history and rundown for each type with a brief date-by-date analysis. Click on individual coins for additional information regarding varieties, populations, availability, and detailed further discussion. There are also front page sections devoted to discussion of: rarity by grade, known mintages, grading, pricing, and literature. Additionally I provide historical information on the coin types leading up to the Dinero. The discussion of these early types is kept to a "type coin" dialogue, focusing on an historical and general overview sans coverage by date and varieties. While I, as any author must, rely on previously written sources (see "Further Reading"), much of the research here is my own.

The Dineros are possibly the most difficult set of decimal Peruvian seated minors to assemble in Uncirculated condition, and probably in circulated grades as well. See the discussion below. While my set is not 100 percent complete, it does boast some great rarities, the centerpiece being the exceedingly rare 1855 Pattern Proof 10 Centimos, of which only a few are known. Other highlights include two Reals that are both the lone finest graded for their type, the rare 1872 Dinero in MS 64, and the rare 1894/3 Dinero in MS 62 (both the finest graded currently in holders), as well as the single year type 1886 Cuzco Dinero in the top grade of MS 62. For any Dineros I don't own or haven't yet sent in for grading, there is still a full write-up for those dates. The exception is the 10 Centavos fiduciary coins of 1879 and 1880. I do not intend to purchase these coins in holders due to their being very common and of low value. See discussion under "Inbetween Years". (Edit: I was able to purchase the lone uber Gem 1879 at reasonable cost and have added it to the set with further information).

Of note: Population reports are accurate as of November 2017. Please remember that nice raw examples still exist in Peru ungraded. Because the 1885 ACC Arequipa Dinero is not listed in Krause, I can not add it, so it will be discussed only on the front page in the date-by-date analysis.

The prices in Krause 1901-2000 have been adjusted recently, but the prices in the 1801-1900 book have not. Keep in mind these 19th Century prices are out-of-date and often too low. With the exception of a couple dates, all Dineros are much more scarce than their 1/2 Dinero counterparts.

Ten Fun Facts You Will Learn When You Read Through My Set:

- Which Dinero has a letter punched in facing 90 degrees in the wrong direction?

- In which year was the Dinero struck on one day only?

- Why do the Dineros of 1900-1903 have so many overdates?

- Which Peruvian coins were designed by James Longacre and stuck at the Philadelphia Mint (known as the very first coins struck in the United States for a foreign government)?

- Which Dinero has a word spelled incorrectly?

- Which Dinero is listed in the Standard Catalog but only known as a counterfeit?

- Why was a Dinero struck in Cuzco for only one year?

- Why was a Spanish Real struck in Peru after the country declared Independance?

- In what year did a mint employee mistakenly use a "1" punch for an "I"?

- Why did the assayer's initials go from "TF" to just "F" in 1896?

- Bonus eleventh fact: Which Dinero is known to be unique...just one known?

Historical Background and Date By Date Discussion By Type

Eight Types of Antecedants: 1/8 Pesos, Royalist Reals struck in Independant Peru, and the early Standing Reals

We begin with the nascent modern state of Peru fighting for it's survival. The following Reals and 1/8 Peso are the precursors to the Dinero. When Peru moved to a decimal system in 1858-1863, this denomination was re-named, re-valued at 10 cents from the previous 12 1/2 cents, and had it's diameter reduced as well as its weight (from 3.38 grams to 2.5 grams). Yet the Dinero was still a coin the general public knew as the "Real". Let's begin:

Though Peru declared Independence in 1821, the Royalist forces took Lima for one month in 1823 and struck Reals (as well as other denominations) of Ferdinand VII at the Lima mint. This type was struck 1811-1821 and 1823. All dates are rare in high grades, especially the 1823. The 1823 Real is the last Spanish Real struck at the Lima mint.

On their way out, the Royalists absconded with the Lima mint machinery and set the building ablaze. They then brought forth a "provisional mint" in Cuzco in 1824 and struck Royalist Reals there (as well as 2 and 8 Reales). This mint would later strike coins of Independent Peru beginning in 1826. 1824 Reals are very scarce in any grade; I have never seen a mint state example. These Cuzco 1824 Reals are the very last of the Spanish Reals struck in Peru.

While these Spanish incursions were occurring, independent Peru was also striking its first coins in 1822-1823; this was a stop-gap provisional coinage to provide small coin for circulation. One of these was the copper 1/8 Peso. The 1/8 Peso was valued at 12 1/2 Cents, matching the value of the Real at the time. These "Octavo De Peso", as well as the "Quarto De Peso" were reportedly restruck in 1921 as part of the 100th Anniversary of Independence celebration. No clear way of distinguishing between original and restrikes is known. However, those 1/8 Pesos with the letter "V" are less likely to be restrikes. 1/8 Pesos are generally available in circulated grades, though they are more scare than the 1/4 Pesos. Planchet pitting and weak strikes are the norm. Please see further discussion on the 1823 1/8 Peso page for a complete history.

Regular coinage of Reals started in 1826. There are five types of these standing liberty Reals. Type 1 was struck from 1826-1840 in Lima. Type 2 was struck 1841-1856. This is the same as the first type with the addition of the fineness of the silver noted on the reverse. The fineness was added to aid in identifying the "good" coins versus the debased moneda feble. Type 3 was struck from 1827 until 1831 in Cuzco (abbreviated "CUZ" on the coins). Type 4 was struck in 1834. It is the same as type 3, except the word Cuzco is spelled in full rather than "CUZ". Type 5 is the 1838 Real of North Peru, struck during the years of the Peru-Bolivian Confederation, which says "NOR-PERUANO" on the reverse.

Most existing standing liberty Reals are in low grade. Type 2 is the most available in mint state, but still very scarce. Type 1 is rare in mint state, though some examples do exist. Note: The Krause catalog states that the 1835/3 is "reported, not confirmed". In actuality, I have seen many examples of this date.

The Cuzco Reals are unknown in mint state (bar one UNC Details 1831), and are very rare in any grade. None of any date have been straight graded at NGC! The 1838 North Peru Real is scarce, but not nearly as rare as previously thought. While auction catalogs report there are 3 to 6 known, 15-25 would seem to be the more accurate number. Most examples are lower grade, however there is one very attractive raw mint state specimen in a museum in Peru.

Towards the Dinero: 1855 Pattern and Reals 1859-1861

The monetary situation was dire in 1850's Peru. Bolivian debased coins, or "Moneda Feble" made up the bulk of circulating coin in the country, counterfeits of good Peruvian coin were rampant (due to an overly simple design that wore quickly, counterfeits were not much of a challenge to pass), and technical problems plagued the mint in Lima. What .903 fine silver coin was struck by Peru was mostly exported to foreign markets, leaving the country awash in debased Feble. Peru's neighbor to the South, Chile, moved to a Decimal monetary system in 1852, a move that cause the wheels of change to slowly churn in Peru.

For many years the country bickered about how best to amortize the Feble. Various new policies were enacted to clean up the Peruvian money. New minting equipment arrived from the US in 1855 so as produce more uniform coins. The Pasco mint was shuttered in order to focus efforts at uniformity in Lima.

Pattern Proof 10 Centimos were produced by the United States for Peru in 1855 along with other denominations as a preparatory step towards a new Decimal coinage. These featured the same design as the then current "Pesos of Castilla" and were the first coins struck by the US for a foreign state. Only a few of these Proofs survive. These 10 Centimos, as well as the forthcoming Reals and Dineros, are all the diameter of a US dime, and valued at 10 Cents. The old-style Reals were close in size to a US nickel, but much thinner, and valued at 12 1/2 cents.

The law of 1857, though never fully implemented, was the important next step. It was proposed to stop accepting the Feble at nominal value. There was to be a new Decimal coinage of 100 Centisimos to the Peso. The 20 Centavo piece was to be the "Peseta", a term resurrected in 1880.

The coinage struck in semi-accordance with the Law of 1857 are now known as the "Transitionals". Importantly, in 1858, a talented engraver was hired from Great Britain. Only 25, Robert Britten, a former apprentice and teacher at the Birmingham Mint, brought expertise that was sorely lacking in the engraving department. He was to be the engraver for the transitional Reals of 1859-1861, and the forthcoming Dineros. His work was of very high artistic capability compared to other Latin American engravers of the day.

The first coins of the transitional series were the 1858 1/2 Real and 50 Centimos, of the old "Peso of Castilla" design. These were struck from hubs produced in the US. These coins brought a premium in the marketplace and were quickly exported making little dent in Peru's monetary crisis. Next came the 50 Centavos of 1858-59. Because silver was on the rise, these were also largely exported.

The Reals, first appearing in 1859, were the transitional coin between the old Reales and the new Dineros. These featured a Seated Liberty design by engraver Robert Britten, a British transplant to Peru, which was to be slightly tweaked for the future Dineros. 1859's are rarely seen. 1860 is the available Real, but the number of survivors are much smaller than for the very common 1860 1/2 Real, and can be a considerable challenge to find in Gem. The 1861 featured a slightly altered reverse, now with bent leaves. This date is rare in all grades, and even more difficult than the 1859.

The transitionals were both success and failure. Much more uniform than the previous circulating coinage, these new designs largely thwarted counterfeiters. However, a great many varieties exist with these coins, with varying weights being reported.

The First Dineros - Early Type Dineros: 1863-1877

The new Dineros, designed by Britten, were of the same diameter and a similar design as the previous transitional Reals. The overall design was flattened slightly, and design elements on the reverse were now more compact. The overall aesthetic of the Reals was a bit more pleasing. Although these coins had a new name, the "Dinero", the public still often referred to them by the old Spanish nomenclature: Reals. Robert Britten's initials can be found on the early Dineros to the left of the shield in the rock. The new decimal coins were part of a bi-metallic monetary system which placed the value of gold to silver at 20:1.

Many early dates come in a diversity of die varieties, with each coin being more individualistic than the somewhat more streamlined coins of later years. Overall, circulated examples are readily available for many early Dinero dates. Uncirculated coins are much more challenging and under-appreciated, however.

In the first year of Dineros, 1863, the mint took great care in producing these coins. They often come well struck and with good luster in mint state. With the 1864 Dineros, the mint became more sloppy with it's letter and numeral punches. Varieties abound for this year; in fact the most varieties for any Dinero in the whole series. Of most interest are an 1864 Dinero with a "1" used as an "I" in DINO and one with a Roman "1" used in the date. During the year, the colon following REPUB was changed to a period. Both types are found on Dineros of 1864. The 1863 Dinero is more available in mint state with the 1864 being scarce. The 1865 Dinero is scarce in all grades, and I have not yet seen a mint state example. Varieties include a Roman "1" and 1865/3. I am skeptical of the reported 1865 6/5.

1866 is very common in circulated grades, which are always available. However, high end mint-state specimens are more challenging. Myriad dies were used to strike this date. There is an unconfirmed 1867 Dinero listed in the standard catalog. No research has yet shown evidence of a genuine coin of this year. By 1867, the introduction of small decimal coins, including the Dinero, had aided in the full conversion of the debased moneda feble.

The 1870's saw the mint in Lima struggling with it's ill-kept machinery to keep up with the need for small coin in Peru, even after new hardware was installed. By 1872, silver was the de facto legal coinage, and as the price of silver began to depreciate, all gold coin was exported. By the end of the decade, private bank paper money was to be the main circulating tender. Most 1870 Dineros are struck over old dies from the 1860's, showing a 7/6 in the date. In this year the assayer initials changed from YB to YJ. Jose Agustin Figueroa (J) replaced Bernardo Aguilar (B). Aguilar had served since the early 1830's, first at branch mints and then at Lima. Figueroa was to serve a long term until his death in 1907 from tuberculosis. Many 1870's also show a J struck over the old die's B. See discussion under the 1870 Dinero for more information on additional varieties. any 1870 Dinero in true mint state is a good find.

The 1872 Dinero was struck on only one day and is a key date for the entire Dinero series. Circulated examples only come up for auction perhaps one or two times (or less) a year, and mint state examples are rare. All 1872 Dineros are struck over older dies, showing a 7/6 and J/B. The "regular" date in Krause can be ignored. Both the 1874 and 1875 Dineros are easy to find in circulated grades. The later is the most available early Dinero in mint state, while the former is a touch more challenging to locate. In 1874 the dot under the "O" in DINO was replaced by a bar. The three main varieties for the 1874 are thus: with dot, with bar, and with bar and Roman "1". The 1874's with dot are quite scarce. Curiously, the 1875's only have very minor varieties despite the larger numbers struck. 1877 is less available then some of the more common early dates, but it does sometimes appear in low-end mint state. There is a neat error of 1877 where "FELIZ" is spelled "FEILZ".

Inbetween Years: Provisional 10 Centavos, Arequipa and Cuzco Mints Re-open, and the 1886 Proof Dineros

The 1880's were a chaotic time for Peru's monetary system, in large part due to the effects of the War of the Pacific on the country early in the decade. The 1879 and 1880 10 Centavos provisional coins, featuring a sun-face on the obverse, were temporary copper-nickel (75 percent copper, 25 percent nickel) replacements for the Dinero, issued to provide a small coin replacement for the circulating fractional paper money. These were a touch larger than a US nickel (22.3 mm rather than 21. 2 mm) and just a smidge over the 5 gram weight of the nickel. They were manufactured in Brussels in large numbers (see mintages below). Both dates are extremely common, with nice raw mint state examples always available. Sellers often mark-up holdered examples well beyond their real value. The 1879 is seemingly difficult in Gem or better, with only one coin at NGC graded in MS 66 (none in 65), and one each in 66 and 67 at PCGS, however I believe there to be some raw Gems in the market. What is in theory very rare is the 1880 Proof 10 Centavos, of which I only know of one coin. It is in a PCGS PF 64 holder, and sold at Heritage in June 2006 for $59. Further information on this proof coin (and the 1879 Proof 5 Centavos) is absent. A strong possibility exists that these proof coins are label errors by PCGS, yet these proofs are listed in Krause. Krause can be wrong, however. It would be odd for Brussels to strike a proof of one denomination in 1879 and the other in 1880. If this coin came to market today, and is a true proof, I would expect it to bring exponential multiples of that paltry number. My belief, though, is they are unlikely to be proof strikings. The other provisional coins were the 1879 and 1880 5 Centavos and 1879 20 Centavos.

No Dineros were minted in Lima between 1877 and 1888. Small coin was desperately needed during the civil war period of 1884-1885 following the War of the Pacific. The Arequipa Mint was re-opened in 1885, decreed to only mint Dineros and 1/5 Sols to fill this need. The Mint only operated a few months. Problems with the machinery and the low quality of the produced coins lead to it's closure. The 1885 Arequipa 1/5 sols are extremely rare, with perhaps only 10 or so now known. The 1885 Dinero is exceedingly rare, and is believe to be unique. A photo of both sides of this coin can be seen in Volume VI of Flatt's "The Coins of Independent Peru". The reverse is also the cover photo for Yabar's 1996 book (see Further Reading for more information). This coin is very similar to Lima minted Dineros, but more crude. The Dinero is not listed in Krause, but needs to be. To the left of the shield of the 1885 Dinero is the name GAMBOA. Enrique A. Gamboa was the head of operation. Flatt believes the assayer initials A.A.C. on the reverse may be the initials of Alejandro A. Caballero. Only the initials A.C. appear on the 1/5 Sol of 1885. I have been told by an associate in Peru that the unique 1885 Arequipa Dinero resides with a collector who cleans all his coins!

The Cuzco mint was also re-opened in 1885 in an attempt to replace the "cut" coins then circulating. They struck 1/2 Dineros in 1885 and Dineros in 1886. 1886 Dineros are scarce, but traceable in grades below XF, and often come cleaned. Their somewhat crude and flat design wore quickly in the public's hand. Mint state examples are very rare. They come in varieties with or without initials to the left of the shield on the obverse, and differences in the "1" in the date on the reverse.

Also in 1886, further steps were taken to ensure proper minor circulating coins were available. Pitiful numbers of primitive looking small coin were coming from the briefly re-opened Cuzco and Arequipa Mints, the engraver Robert Britten had passed in 1882, and the Lima Mint had damaged or missing equipment following the War. Peru looked towards Great Britain for help. Leonard C. Wyon at the Royal Mint was contracted to produce matrices for new Seated Liberty coins. These matrices ended up being the wrong diameter, and thus were not able to be used other than to strike six Proof versions of each denomination. The Proof 1886 Dineros are very rare and almost never seen on the market.

1888-1892: A New Beginning

Someone attempting a Dinero set by type in Uncirculated grades may become frustrated by the dirth of available examples from these years. The design was fully reworked from the 1863-1877 type. The matrices based on the 1886 Pattern Proof were the wrong diameter, and were thus not used. The new design imitated very closely the obverse of the 1886 Pattern with LIBER-TAD excuse, but with a much smaller shield and wreath on the reverse.

The 1888 Dinero is the rarest Lima mint date/assayer coin of, not just the Dinero series, but of all Peruvian silver series 1858-1935. In any given year, it is likely no examples will be offered. See the 1888 page for a complete census. The 1890 is the only available date, and even then, is still very scarce in mint state. Only four have been graded. I have identified four types of 1890's; please see the 1890 page for further discussion. The 1891 and 1892 are also rare in all grades, especially the 1892. Only one 1891 has been graded; none for 1892; both are undervalued. 1890 and 1891 come with a curved or flat-top "1" in the date; 1888 and 1892 with only flat top.

1893-1903: Liber-tad Sinks In and UN DINO Gets Curvy

In 1893, the design was tweaked; LIBER-TAD became incuse, UN DINO became a curved rather than straight line, and the overall aesthetic became "mushier". It is not clear why re-worked matrices were made in this year. The coins of 1893 through 1895 are all fairly difficult in most grades. The 1893 is the most available of the three, appearing in lower-end mint state on occasion. The 1894 is one of most rare and expensive dates in the entire series. Most all 1894's appear to be the overdate 1894/3. Flatt does show photographic evidence of a plain date, however. The 1895 Dinero is difficult in all grades and almost never seen without wear. 1896 TF rarely appears in better condition on the market, though some very high end MS 67 coins have been graded, which is not true for the 1896 F, another scarce coin, which is more available in lower-end mint state than the "TF". A rare and eye-catching error of the 1896 F shows the "E" in FIRME rotated 90 degrees to the right. 1897 and 1898 are underrated dates. Both 1897 JF and VN are rarely seen in Uncirculated condition, although a few of each are graded. A small group of mint state 1898 Dineros has been sold on a foreign site, but other than those, this date is not often seen. Some come with a bold error: D/F in DINO. No Dineros were struck in 1899, though counterfeits may exist.

A word on the assayer initials: "TF" stood for Torrico y Mesa and Juan Figueroa. The law was changed in the 1896 to allow just one head assayer. Juan Figueroa was the man left standing, and only his initial "F" is seen on some coins of 1896. In 1897, the mint began using two initials for the assayer, thus "JF" for Juan Figueroa, or "VN" for Vicente Novoa (in 1897 only when the assistant assayer took over coining duties). 1897 also marketed the year Peru converted to the Gold standard. The value of silver had dropped by half since the early 1880's, necessitating a new standard. Starting in 1897, small coin, including Dineros, was made from melted down Soles.

The design was again to be tweaked for the Dinero in 1904 (1901 for the 1/5 Sol; 1907 for the 1/2 Dinero). Before this changeover, dies were used from previous 19th Century years to strike the Dineros of 1900, 1902, and 1903, causing a rash of various overdates. 1900 and 1903 are much more available than most previous dates of the 1890's, although finding Gem examples of the 1903 may prove difficult, and none have yet been graded. The 1902 is an underrated year, with only five examples graded in mint state at PCGS/NGC. No Dineros were minted in 1901; beware coins with altered dates.

1904-1916: The Final Years

These later date Dineros are overall the most available and easily findable in Uncirculated grades. There are, however, a few sleepers in the midst and rare varieties. The design was reworked in subtle ways. The lettering becomes more streamlined, less "chunky," and the elements of the reverse shield are re-engraved. The wreath above the shield is also remade with a new texture. The Seated Liberty herself is largely similar, but has a more "crisp" look about her.

1904 is an underrated date in mint state, although available with some searching. Gems are rare. 1905 and 1906 are both available in nice Uncirculated. The former is the only real "hoard" Dinero (a small hoard of about 200 coins). It often comes extremely nice with intense Prooflike fields.

In 1907 Francisco Gamara (initials FG) replaced the long-tenured Figueroa as assayer. Figueroa had passed away from tuberculosis. 1907 FG is easily findable in higher grades, though not in Gem. The 1907 JF is believed to be counterfeit only (despite one example being graded at NGC. I believe this is most likely a typo). Dineros of 1907 through 1913 may feature a dot below the O in DINO in various placement, or lack said dot. The new assayers initials FG are also commonly punched over old dies with the JF initals. See further discussion under individual coins for more specifics on these varieties; some dates are rare with or without dot. Some "non-sense" over-lettering is reported.

The 1908 Dinero is generally traceable in most grades through low-end Uncirculated, but tougher in Gem. 1909 is the Key to the later dates, and is rarely seen in true mint state. 1910 and 1911 are moderately better dates; they may take some time to find if you are looking for a high-end example. 1912 and 1913 are more available in all grades. No Dineros were minted in 1914 or 1915, as World War I began (though other denominations were struck in these years). 1916 sees the final year of the Dinero. Although this date is traceable in high-end mint state with some searching, it's not quite as easy to find as the low Standard Catalogue pricing would have one believe. The Dinero is overshadowed by it's exceedingly common 1/2 Dinero cousin of the same date. The 1916 Dinero comes in Small Date and Large Date varieties. The later is seemingly very scarce, although these two date sizes are confusing (see further discussion under my 1916 Dinero).

The price of silver began a strong recovery in 1916 and into 1917. 1917 was to be the last of the 90 percent silver decimal coins minted in Peru. The Dinero was replaced by the copper-nickel 10 Centavo piece in 1918. These featured a "cereal head" woman on the obverse, and a simplistic design on the reverse sans the Peruvian Coat of Arms. The 10 Centavos were to see many changes in composition, location where struck, thickness, and design before the "cereal head" design was finally retired in 1965. They are a set of coins in need of deeper research.

Rarity by Date in Gem Mint State

These comments are based on my experience viewing raw Dineros and the population reports.

Some dates are common through MS 64, but unavailable in Gem condition.

1855 Pattern Proof 10 Centimos - May Not Exist

1859 Real - May Not Exist

1860 Real - Very Scarce

1861 Real - May Not Exist

1863 - Scarce

1864 - Rare

1865 - May Not Exist

1866 - Rare

1870 - May Not Exist

1872 - Exceedingly Rare

1874 - Very Scarce

1875 - Scarce

1877 - Rare

1879 10 Centavos - Common

1880 10 Centavos - Common

1886 JM Cuzco - May Not Exist

1886 Pattern Proof - Extremely Rare

1888 - May Not Exist

1890 - Rare

1891 - May Not Exist

1892 - Exceedingly Rare

1893 - Extremely Rare, May Not Exist

1894 - May Not Exist

1895 - Exceedingly Rare

1896 TF - Scarce

1896 F - Rare

1897 VN - Very Scarce

1897 JF - Very Scarce

1898 - Rare

1900 - Common

1902 - Very Rare

1903 - Very Rare

1904 - Rare

1905 - Common

1906 - Somewhat Common

1907 FG - Scarce

1908 - Somewhat Scarce

1909 - Rare

1910 - Somewhat Scarce

1911 - Scarce

1912 - Somewhat Scarce

1913 - Somewhat Common

1916 - Common

Rarity by Date in Low-End Mint State MS 61-MS 63

1855 Pattern Proof 10 Centimos - Exceedingly Rare

1859 Real - Rare

1860 Real - Somewhat scarce

1861 Real - Very Rare

1863 - Somewhat Scarce

1864 - Scarce

1865 - May Not Exist

1866 - Somewhat Scarce

1870 - Very Scarce

1872 - Very Rare

1874 - Scarce

1875 - Somewhat Scarce

1877 - Somewhat Scarce

1879 10 Centavos - Common

1880 10 Centavos - Common

1886 JM Cuzco - Very Rare

1886 Pattern Proof - Extremely Rare

1888 - Extremely Rare

1890 - Very Scarce

1891 - Very Rare

1892 - Very Rare

1893 - Scarce

1894 - Very Rare

1895 - Rare

1896 TF - Very Scarce

1896 F - Somewhat Scarce

1897 VN - Scarce

1897 JF - Scarce

1898 - Somewhat Scarce

1900 - Common

1902 - Somewhat Scarce

1903 - Common

1904 - Somewhat Scarce

1905 - Common

1906 - Somewhat Common

1907 FG - Common

1908 - Somewhat Scarce

1909 - Scarce

1910 - Somewhat Scarce

1911 - Somewhat Scarce

1912 - Somewhat Common

1913 - Common

1916 - Common

Rarity by Date in Circulated Grades Good through About Uncirculated

1855 Pattern Proof 10 Centimos - None May Have Circulated

1859 Real - Very Scarce

1860 Real - Somewhat Common

1861 Real - Rare

1863 - Somewhat Common

1864 - Common

1865 - Scarce

1866 - Common

1870 - Somewhat Scarce

1872 - Very Scarce

1874 - Somewhat Common

1875 - Common

1877 - Somewhat Scarce

1879 10 Centavos - Common

1880 10 Centavos - Common

1886 JM Cuzco - Somewhat Scarce

1886 Pattern Proof - None May Have Circulated

1888 - Very Rare

1890 - Scarce

1891 - Very Scarce

1892 - Rare

1893 - Somewhat Scarce

1894 - Rare

1895 - Very Scarce

1896 TF - Scarce

1896 F - Somewhat Scarce

1897 VN - Somewhat scarce

1897 JF - Somewhat Scarce

1898 - Somewhat Scarce

1900 - Common

1902 - Scarce

1903 - Common

1904 - Scarce

1905 - Common

1906 - Common

1907 FG - Common

1908 - Somewhat Common

1909 - Scarce

1910 - Somewhat scarce

1911 - Somewhat Scarce

1912 - Somewhat Common

1913 - Common

1916 - Common

Known Mintages

Any date not listed has an unknown mintage. Mintages across the board are very small by United States standards. Overall, reported mintages do tend to correspond to current scarcity. But most Dineros circulated and many were eventually melted, leaving many fewer survivors than the mintages would suggest.

While the 1890 Dinero is not exceedingly rare, the mintage would suggest a more common coin than actually exists. Lower mintage coins in the last few years of a coin series are more likely to survive in high grades, as they didn't have time to circulate and may have been kept as a memento of the "old type".

1855 Pattern - 6

1879 10 Centavos - 3,005,000

1880 10 Centavos - 4,000,000

1886 Pattern - 6

1888 - 10,000

1890 - 400,000

1891 - 60,000

1892 - 69,000

1893 - 23,000

1895 - 90,000

1896 - 534,000 (Both assayers)

1897 - 510,500 (both assayers)

1898 - 200,000

1900 - 550,000

1902 - 374,500

1903 - 887,000

1904 - 380,000

1905 - 700,000

1906 - 826,000

1907 - 500,000

1908 - 200,000

1910 - 210,000

1911 - 200,000

1912 - 400,000

1913 - 360,000

1916 - 430,000

Grading Mint State Dineros, Die/Planchet Issues, and High Points of the Design

High Points on Dineros:

Judging wear on early Dineros is more difficult than on the larger decimal denominations where first points of contact are more obvious. US collectors may assume the leg/knee as a good point of reference, but this would be in error. The leg is not a high point, and is often weakly struck so as to confuse some into believing wear is present when it is not. The best places to look on early Dineros are Liberty's hair curls and cheek, and her shall near her breast and shoulder on the obverse. The reverse is fairly unreliable for judging wear on AU coins, but the sides of the leaves to the right of the shield and the center of the cornucopia are high points. Yet, these areas are often weakly struck. On borderline coins, I mainly look to see if the luster is broken or not. On Dineros of the 1890's and later, the elbow is higher and may be a first point of wear. The breast is also higher, but is often weakly struck. On the reverse of the later Dineros, look at the bottom of the center leaf directly to the right of the cornucopia.

Planchet and Die Issues Seen on Dineros that may effect the grade:

Historical Background and Date By Date Discussion By Type

Eight Types of Antecedants: 1/8 Pesos, Royalist Reals struck in Independant Peru, and the early Standing Reals

We begin with the nascent modern state of Peru fighting for it's survival. The following Reals and 1/8 Peso are the precursors to the Dinero. When Peru moved to a decimal system in 1858-1863, this denomination was re-named, re-valued at 10 cents from the previous 12 1/2 cents, and had it's diameter reduced as well as its weight (from 3.38 grams to 2.5 grams). Yet the Dinero was still a coin the general public knew as the "Real". Let's begin:

Though Peru declared Independence in 1821, the Royalist forces took Lima for one month in 1823 and struck Reals (as well as other denominations) of Ferdinand VII at the Lima mint. This type was struck 1811-1821 and 1823. All dates are rare in high grades, especially the 1823. The 1823 Real is the last Spanish Real struck at the Lima mint.

On their way out, the Royalists absconded with the Lima mint machinery and set the building ablaze. They then brought forth a "provisional mint" in Cuzco in 1824 and struck Royalist Reals there (as well as 2 and 8 Reales). This mint would later strike coins of Independent Peru beginning in 1826. 1824 Reals are very scarce in any grade; I have never seen a mint state example. These Cuzco 1824 Reals are the very last of the Spanish Reals struck in Peru.

While these Spanish incursions were occurring, independent Peru was also striking its first coins in 1822-1823; this was a stop-gap provisional coinage to provide small coin for circulation. One of these was the copper 1/8 Peso. The 1/8 Peso was valued at 12 1/2 Cents, matching the value of the Real at the time. These "Octavo De Peso", as well as the "Quarto De Peso" were reportedly restruck in 1921 as part of the 100th Anniversary of Independence celebration. No clear way of distinguishing between original and restrikes is known. However, those 1/8 Pesos with the letter "V" are less likely to be restrikes. 1/8 Pesos are generally available in circulated grades, though they are more scare than the 1/4 Pesos. Planchet pitting and weak strikes are the norm. Please see further discussion on the 1823 1/8 Peso page for a complete history.

Regular coinage of Reals started in 1826. There are five types of these standing liberty Reals. Type 1 was struck from 1826-1840 in Lima. Type 2 was struck 1841-1856. This is the same as the first type with the addition of the fineness of the silver noted on the reverse. The fineness was added to aid in identifying the "good" coins versus the debased moneda feble. Type 3 was struck from 1827 until 1831 in Cuzco (abbreviated "CUZ" on the coins). Type 4 was struck in 1834. It is the same as type 3, except the word Cuzco is spelled in full rather than "CUZ". Type 5 is the 1838 Real of North Peru, struck during the years of the Peru-Bolivian Confederation, which says "NOR-PERUANO" on the reverse.

Most existing standing liberty Reals are in low grade. Type 2 is the most available in mint state, but still very scarce. Type 1 is rare in mint state, though some examples do exist. Note: The Krause catalog states that the 1835/3 is "reported, not confirmed". In actuality, I have seen many examples of this date.

The Cuzco Reals are unknown in mint state (bar one UNC Details 1831), and are very rare in any grade. None of any date have been straight graded at NGC! The 1838 North Peru Real is scarce, but not nearly as rare as previously thought. While auction catalogs report there are 3 to 6 known, 15-25 would seem to be the more accurate number. Most examples are lower grade, however there is one very attractive raw mint state specimen in a museum in Peru.

Towards the Dinero: 1855 Pattern and Reals 1859-1861

The monetary situation was dire in 1850's Peru. Bolivian debased coins, or "Moneda Feble" made up the bulk of circulating coin in the country, counterfeits of good Peruvian coin were rampant (due to an overly simple design that wore quickly, counterfeits were not much of a challenge to pass), and technical problems plagued the mint in Lima. What .903 fine silver coin was struck by Peru was mostly exported to foreign markets, leaving the country awash in debased Feble. Peru's neighbor to the South, Chile, moved to a Decimal monetary system in 1852, a move that cause the wheels of change to slowly churn in Peru.

For many years the country bickered about how best to amortize the Feble. Various new policies were enacted to clean up the Peruvian money. New minting equipment arrived from the US in 1855 so as produce more uniform coins. The Pasco mint was shuttered in order to focus efforts at uniformity in Lima.

Pattern Proof 10 Centimos were produced by the United States for Peru in 1855 along with other denominations as a preparatory step towards a new Decimal coinage. These featured the same design as the then current "Pesos of Castilla" and were the first coins struck by the US for a foreign state. Only a few of these Proofs survive. These 10 Centimos, as well as the forthcoming Reals and Dineros, are all the diameter of a US dime, and valued at 10 Cents. The old-style Reals were close in size to a US nickel, but much thinner, and valued at 12 1/2 cents.

The law of 1857, though never fully implemented, was the important next step. It was proposed to stop accepting the Feble at nominal value. There was to be a new Decimal coinage of 100 Centisimos to the Peso. The 20 Centavo piece was to be the "Peseta", a term resurrected in 1880.

The coinage struck in semi-accordance with the Law of 1857 are now known as the "Transitionals". Importantly, in 1858, a talented engraver was hired from Great Britain. Only 25, Robert Britten, a former apprentice and teacher at the Birmingham Mint, brought expertise that was sorely lacking in the engraving department. He was to be the engraver for the transitional Reals of 1859-1861, and the forthcoming Dineros. His work was of very high artistic capability compared to other Latin American engravers of the day.

The first coins of the transitional series were the 1858 1/2 Real and 50 Centimos, of the old "Peso of Castilla" design. These were struck from hubs produced in the US. These coins brought a premium in the marketplace and were quickly exported making little dent in Peru's monetary crisis. Next came the 50 Centavos of 1858-59. Because silver was on the rise, these were also largely exported.

The Reals, first appearing in 1859, were the transitional coin between the old Reales and the new Dineros. These featured a Seated Liberty design by engraver Robert Britten, a British transplant to Peru, which was to be slightly tweaked for the future Dineros. 1859's are rarely seen. 1860 is the available Real, but the number of survivors are much smaller than for the very common 1860 1/2 Real, and can be a considerable challenge to find in Gem. The 1861 featured a slightly altered reverse, now with bent leaves. This date is rare in all grades, and even more difficult than the 1859.

The transitionals were both success and failure. Much more uniform than the previous circulating coinage, these new designs largely thwarted counterfeiters. However, a great many varieties exist with these coins, with varying weights being reported.

The First Dineros - Early Type Dineros: 1863-1877

The new Dineros, designed by Britten, were of the same diameter and a similar design as the previous transitional Reals. The overall design was flattened slightly, and design elements on the reverse were now more compact. The overall aesthetic of the Reals was a bit more pleasing. Although these coins had a new name, the "Dinero", the public still often referred to them by the old Spanish nomenclature: Reals. Robert Britten's initials can be found on the early Dineros to the left of the shield in the rock. The new decimal coins were part of a bi-metallic monetary system which placed the value of gold to silver at 20:1.

Many early dates come in a diversity of die varieties, with each coin being more individualistic than the somewhat more streamlined coins of later years. Overall, circulated examples are readily available for many early Dinero dates. Uncirculated coins are much more challenging and under-appreciated, however.

In the first year of Dineros, 1863, the mint took great care in producing these coins. They often come well struck and with good luster in mint state. With the 1864 Dineros, the mint became more sloppy with it's letter and numeral punches. Varieties abound for this year; in fact the most varieties for any Dinero in the whole series. Of most interest are an 1864 Dinero with a "1" used as an "I" in DINO and one with a Roman "1" used in the date. During the year, the colon following REPUB was changed to a period. Both types are found on Dineros of 1864. The 1863 Dinero is more available in mint state with the 1864 being scarce. The 1865 Dinero is scarce in all grades, and I have not yet seen a mint state example. Varieties include a Roman "1" and 1865/3. I am skeptical of the reported 1865 6/5.

1866 is very common in circulated grades, which are always available. However, high end mint-state specimens are more challenging. Myriad dies were used to strike this date. There is an unconfirmed 1867 Dinero listed in the standard catalog. No research has yet shown evidence of a genuine coin of this year. By 1867, the introduction of small decimal coins, including the Dinero, had aided in the full conversion of the debased moneda feble.

The 1870's saw the mint in Lima struggling with it's ill-kept machinery to keep up with the need for small coin in Peru, even after new hardware was installed. By 1872, silver was the de facto legal coinage, and as the price of silver began to depreciate, all gold coin was exported. By the end of the decade, private bank paper money was to be the main circulating tender. Most 1870 Dineros are struck over old dies from the 1860's, showing a 7/6 in the date. In this year the assayer initials changed from YB to YJ. Jose Agustin Figueroa (J) replaced Bernardo Aguilar (B). Aguilar had served since the early 1830's, first at branch mints and then at Lima. Figueroa was to serve a long term until his death in 1907 from tuberculosis. Many 1870's also show a J struck over the old die's B. See discussion under the 1870 Dinero for more information on additional varieties. any 1870 Dinero in true mint state is a good find.

The 1872 Dinero was struck on only one day and is a key date for the entire Dinero series. Circulated examples only come up for auction perhaps one or two times (or less) a year, and mint state examples are rare. All 1872 Dineros are struck over older dies, showing a 7/6 and J/B. The "regular" date in Krause can be ignored. Both the 1874 and 1875 Dineros are easy to find in circulated grades. The later is the most available early Dinero in mint state, while the former is a touch more challenging to locate. In 1874 the dot under the "O" in DINO was replaced by a bar. The three main varieties for the 1874 are thus: with dot, with bar, and with bar and Roman "1". The 1874's with dot are quite scarce. Curiously, the 1875's only have very minor varieties despite the larger numbers struck. 1877 is less available then some of the more common early dates, but it does sometimes appear in low-end mint state. There is a neat error of 1877 where "FELIZ" is spelled "FEILZ".

Inbetween Years: Provisional 10 Centavos, Arequipa and Cuzco Mints Re-open, and the 1886 Proof Dineros

The 1880's were a chaotic time for Peru's monetary system, in large part due to the effects of the War of the Pacific on the country early in the decade. The 1879 and 1880 10 Centavos provisional coins, featuring a sun-face on the obverse, were temporary copper-nickel (75 percent copper, 25 percent nickel) replacements for the Dinero, issued to provide a small coin replacement for the circulating fractional paper money. These were a touch larger than a US nickel (22.3 mm rather than 21. 2 mm) and just a smidge over the 5 gram weight of the nickel. They were manufactured in Brussels in large numbers (see mintages below). Both dates are extremely common, with nice raw mint state examples always available. Sellers often mark-up holdered examples well beyond their real value. The 1879 is seemingly difficult in Gem or better, with only one coin at NGC graded in MS 66 (none in 65), and one each in 66 and 67 at PCGS, however I believe there to be some raw Gems in the market. What is in theory very rare is the 1880 Proof 10 Centavos, of which I only know of one coin. It is in a PCGS PF 64 holder, and sold at Heritage in June 2006 for $59. Further information on this proof coin (and the 1879 Proof 5 Centavos) is absent. A strong possibility exists that these proof coins are label errors by PCGS, yet these proofs are listed in Krause. Krause can be wrong, however. It would be odd for Brussels to strike a proof of one denomination in 1879 and the other in 1880. If this coin came to market today, and is a true proof, I would expect it to bring exponential multiples of that paltry number. My belief, though, is they are unlikely to be proof strikings. The other provisional coins were the 1879 and 1880 5 Centavos and 1879 20 Centavos.

No Dineros were minted in Lima between 1877 and 1888. Small coin was desperately needed during the civil war period of 1884-1885 following the War of the Pacific. The Arequipa Mint was re-opened in 1885, decreed to only mint Dineros and 1/5 Sols to fill this need. The Mint only operated a few months. Problems with the machinery and the low quality of the produced coins lead to it's closure. The 1885 Arequipa 1/5 sols are extremely rare, with perhaps only 10 or so now known. The 1885 Dinero is exceedingly rare, and is believe to be unique. A photo of both sides of this coin can be seen in Volume VI of Flatt's "The Coins of Independent Peru". The reverse is also the cover photo for Yabar's 1996 book (see Further Reading for more information). This coin is very similar to Lima minted Dineros, but more crude. The Dinero is not listed in Krause, but needs to be. To the left of the shield of the 1885 Dinero is the name GAMBOA. Enrique A. Gamboa was the head of operation. Flatt believes the assayer initials A.A.C. on the reverse may be the initials of Alejandro A. Caballero. Only the initials A.C. appear on the 1/5 Sol of 1885. I have been told by an associate in Peru that the unique 1885 Arequipa Dinero resides with a collector who cleans all his coins!

The Cuzco mint was also re-opened in 1885 in an attempt to replace the "cut" coins then circulating. They struck 1/2 Dineros in 1885 and Dineros in 1886. 1886 Dineros are scarce, but traceable in grades below XF, and often come cleaned. Their somewhat crude and flat design wore quickly in the public's hand. Mint state examples are very rare. They come in varieties with or without initials to the left of the shield on the obverse, and differences in the "1" in the date on the reverse.

Also in 1886, further steps were taken to ensure proper minor circulating coins were available. Pitiful numbers of primitive looking small coin were coming from the briefly re-opened Cuzco and Arequipa Mints, the engraver Robert Britten had passed in 1882, and the Lima Mint had damaged or missing equipment following the War. Peru looked towards Great Britain for help. Leonard C. Wyon at the Royal Mint was contracted to produce matrices for new Seated Liberty coins. These matrices ended up being the wrong diameter, and thus were not able to be used other than to strike six Proof versions of each denomination. The Proof 1886 Dineros are very rare and almost never seen on the market.

1888-1892: A New Beginning

Someone attempting a Dinero set by type in Uncirculated grades may become frustrated by the dirth of available examples from these years. The design was fully reworked from the 1863-1877 type. The matrices based on the 1886 Pattern Proof were the wrong diameter, and were thus not used. The new design imitated very closely the obverse of the 1886 Pattern with LIBER-TAD excuse, but with a much smaller shield and wreath on the reverse.

The 1888 Dinero is the rarest Lima mint date/assayer coin of, not just the Dinero series, but of all Peruvian silver series 1858-1935. In any given year, it is likely no examples will be offered. See the 1888 page for a complete census. The 1890 is the only available date, and even then, is still very scarce in mint state. Only four have been graded. I have identified four types of 1890's; please see the 1890 page for further discussion. The 1891 and 1892 are also rare in all grades, especially the 1892. Only one 1891 has been graded; none for 1892; both are undervalued. 1890 and 1891 come with a curved or flat-top "1" in the date; 1888 and 1892 with only flat top.

1893-1903: Liber-tad Sinks In and UN DINO Gets Curvy

In 1893, the design was tweaked; LIBER-TAD became incuse, UN DINO became a curved rather than straight line, and the overall aesthetic became "mushier". It is not clear why re-worked matrices were made in this year. The coins of 1893 through 1895 are all fairly difficult in most grades. The 1893 is the most available of the three, appearing in lower-end mint state on occasion. The 1894 is one of most rare and expensive dates in the entire series. Most all 1894's appear to be the overdate 1894/3. Flatt does show photographic evidence of a plain date, however. The 1895 Dinero is difficult in all grades and almost never seen without wear. 1896 TF rarely appears in better condition on the market, though some very high end MS 67 coins have been graded, which is not true for the 1896 F, another scarce coin, which is more available in lower-end mint state than the "TF". A rare and eye-catching error of the 1896 F shows the "E" in FIRME rotated 90 degrees to the right. 1897 and 1898 are underrated dates. Both 1897 JF and VN are rarely seen in Uncirculated condition, although a few of each are graded. A small group of mint state 1898 Dineros has been sold on a foreign site, but other than those, this date is not often seen. Some come with a bold error: D/F in DINO. No Dineros were struck in 1899, though counterfeits may exist.

A word on the assayer initials: "TF" stood for Torrico y Mesa and Juan Figueroa. The law was changed in the 1896 to allow just one head assayer. Juan Figueroa was the man left standing, and only his initial "F" is seen on some coins of 1896. In 1897, the mint began using two initials for the assayer, thus "JF" for Juan Figueroa, or "VN" for Vicente Novoa (in 1897 only when the assistant assayer took over coining duties). 1897 also marketed the year Peru converted to the Gold standard. The value of silver had dropped by half since the early 1880's, necessitating a new standard. Starting in 1897, small coin, including Dineros, was made from melted down Soles.

The design was again to be tweaked for the Dinero in 1904 (1901 for the 1/5 Sol; 1907 for the 1/2 Dinero). Before this changeover, dies were used from previous 19th Century years to strike the Dineros of 1900, 1902, and 1903, causing a rash of various overdates. 1900 and 1903 are much more available than most previous dates of the 1890's, although finding Gem examples of the 1903 may prove difficult, and none have yet been graded. The 1902 is an underrated year, with only five examples graded in mint state at PCGS/NGC. No Dineros were minted in 1901; beware coins with altered dates.

1904-1916: The Final Years

These later date Dineros are overall the most available and easily findable in Uncirculated grades. There are, however, a few sleepers in the midst and rare varieties. The design was reworked in subtle ways. The lettering becomes more streamlined, less "chunky," and the elements of the reverse shield are re-engraved. The wreath above the shield is also remade with a new texture. The Seated Liberty herself is largely similar, but has a more "crisp" look about her.

1904 is an underrated date in mint state, although available with some searching. Gems are rare. 1905 and 1906 are both available in nice Uncirculated. The former is the only real "hoard" Dinero (a small hoard of about 200 coins). It often comes extremely nice with intense Prooflike fields.

In 1907 Francisco Gamara (initials FG) replaced the long-tenured Figueroa as assayer. Figueroa had passed away from tuberculosis. 1907 FG is easily findable in higher grades, though not in Gem. The 1907 JF is believed to be counterfeit only (despite one example being graded at NGC. I believe this is most likely a typo). Dineros of 1907 through 1913 may feature a dot below the O in DINO in various placement, or lack said dot. The new assayers initials FG are also commonly punched over old dies with the JF initals. See further discussion under individual coins for more specifics on these varieties; some dates are rare with or without dot. Some "non-sense" over-lettering is reported.

The 1908 Dinero is generally traceable in most grades through low-end Uncirculated, but tougher in Gem. 1909 is the Key to the later dates, and is rarely seen in true mint state. 1910 and 1911 are moderately better dates; they may take some time to find if you are looking for a high-end example. 1912 and 1913 are more available in all grades. No Dineros were minted in 1914 or 1915, as World War I began (though other denominations were struck in these years). 1916 sees the final year of the Dinero. Although this date is traceable in high-end mint state with some searching, it's not quite as easy to find as the low Standard Catalogue pricing would have one believe. The Dinero is overshadowed by it's exceedingly common 1/2 Dinero cousin of the same date. The 1916 Dinero comes in Small Date and Large Date varieties. The later is seemingly very scarce, although these two date sizes are confusing (see further discussion under my 1916 Dinero).

The price of silver began a strong recovery in 1916 and into 1917. 1917 was to be the last of the 90 percent silver decimal coins minted in Peru. The Dinero was replaced by the copper-nickel 10 Centavo piece in 1918. These featured a "cereal head" woman on the obverse, and a simplistic design on the reverse sans the Peruvian Coat of Arms. The 10 Centavos were to see many changes in composition, location where struck, thickness, and design before the "cereal head" design was finally retired in 1965. They are a set of coins in need of deeper research.

Rarity by Date in Gem Mint State

These comments are based on my experience viewing raw Dineros and the population reports.

Some dates are common through MS 64, but unavailable in Gem condition.

1855 Pattern Proof 10 Centimos - May Not Exist

1859 Real - May Not Exist

1860 Real - Very Scarce

1861 Real - May Not Exist

1863 - Scarce

1864 - Rare

1865 - May Not Exist

1866 - Rare

1870 - May Not Exist

1872 - Exceedingly Rare

1874 - Very Scarce

1875 - Scarce

1877 - Rare

1879 10 Centavos - Common

1880 10 Centavos - Common

1886 JM Cuzco - May Not Exist

1886 Pattern Proof - Extremely Rare

1888 - May Not Exist

1890 - Rare

1891 - May Not Exist

1892 - Exceedingly Rare

1893 - Extremely Rare, May Not Exist

1894 - May Not Exist

1895 - Exceedingly Rare

1896 TF - Scarce

1896 F - Rare

1897 VN - Very Scarce

1897 JF - Very Scarce

1898 - Rare

1900 - Common

1902 - Very Rare

1903 - Very Rare

1904 - Rare

1905 - Common

1906 - Somewhat Common

1907 FG - Scarce

1908 - Somewhat Scarce

1909 - Rare

1910 - Somewhat Scarce

1911 - Scarce

1912 - Somewhat Scarce

1913 - Somewhat Common

1916 - Common

Rarity by Date in Low-End Mint State MS 61-MS 63

1855 Pattern Proof 10 Centimos - Exceedingly Rare

1859 Real - Rare

1860 Real - Somewhat scarce

1861 Real - Very Rare

1863 - Somewhat Scarce

1864 - Scarce

1865 - May Not Exist

1866 - Somewhat Scarce

1870 - Very Scarce

1872 - Very Rare

1874 - Scarce

1875 - Somewhat Scarce

1877 - Somewhat Scarce

1879 10 Centavos - Common

1880 10 Centavos - Common

1886 JM Cuzco - Very Rare

1886 Pattern Proof - Extremely Rare

1888 - Extremely Rare

1890 - Very Scarce

1891 - Very Rare

1892 - Very Rare

1893 - Scarce

1894 - Very Rare

1895 - Rare

1896 TF - Very Scarce

1896 F - Somewhat Scarce

1897 VN - Scarce

1897 JF - Scarce

1898 - Somewhat Scarce

1900 - Common

1902 - Somewhat Scarce

1903 - Common

1904 - Somewhat Scarce

1905 - Common

1906 - Somewhat Common

1907 FG - Common

1908 - Somewhat Scarce

1909 - Scarce

1910 - Somewhat Scarce

1911 - Somewhat Scarce

1912 - Somewhat Common

1913 - Common

1916 - Common

Rarity by Date in Circulated Grades Good through About Uncirculated

1855 Pattern Proof 10 Centimos - None May Have Circulated

1859 Real - Very Scarce

1860 Real - Somewhat Common

1861 Real - Rare

1863 - Somewhat Common

1864 - Common

1865 - Scarce

1866 - Common

1870 - Somewhat Scarce

1872 - Very Scarce

1874 - Somewhat Common

1875 - Common

1877 - Somewhat Scarce

1879 10 Centavos - Common

1880 10 Centavos - Common

1886 JM Cuzco - Somewhat Scarce

1886 Pattern Proof - None May Have Circulated

1888 - Very Rare

1890 - Scarce

1891 - Very Scarce

1892 - Rare

1893 - Somewhat Scarce

1894 - Rare

1895 - Very Scarce

1896 TF - Scarce

1896 F - Somewhat Scarce

1897 VN - Somewhat scarce

1897 JF - Somewhat Scarce

1898 - Somewhat Scarce

1900 - Common

1902 - Scarce

1903 - Common

1904 - Scarce

1905 - Common

1906 - Common

1907 FG - Common

1908 - Somewhat Common

1909 - Scarce

1910 - Somewhat scarce

1911 - Somewhat Scarce

1912 - Somewhat Common

1913 - Common

1916 - Common

Known Mintages

Any date not listed has an unknown mintage. Mintages across the board are very small by United States standards. Overall, reported mintages do tend to correspond to current scarcity. But most Dineros circulated and many were eventually melted, leaving many fewer survivors than the mintages would suggest.

While the 1890 Dinero is not exceedingly rare, the mintage would suggest a more common coin than actually exists. Lower mintage coins in the last few years of a coin series are more likely to survive in high grades, as they didn't have time to circulate and may have been kept as a memento of the "old type".

1855 Pattern - 6

1879 10 Centavos - 3,005,000

1880 10 Centavos - 4,000,000

1886 Pattern - 6

1888 - 10,000

1890 - 400,000

1891 - 60,000

1892 - 69,000

1893 - 23,000

1895 - 90,000

1896 - 534,000 (Both assayers)

1897 - 510,500 (both assayers)

1898 - 200,000

1900 - 550,000

1902 - 374,500

1903 - 887,000

1904 - 380,000

1905 - 700,000

1906 - 826,000

1907 - 500,000

1908 - 200,000

1910 - 210,000

1911 - 200,000

1912 - 400,000

1913 - 360,000

1916 - 430,000

Grading Mint State Dineros, Die/Planchet Issues, and High Points of the Design

High Points on Dineros:

Judging wear on early Dineros is more difficult than on the larger decimal denominations where first points of contact are more obvious. US collectors may assume the leg/knee as a good point of reference, but this would be in error. The leg is not a high point, and is often weakly struck so as to confuse some into believing wear is present when it is not. The best places to look on early Dineros are Liberty's hair curls and cheek, and her shall near her breast and shoulder on the obverse. The reverse is fairly unreliable for judging wear on AU coins, but the sides of the leaves to the right of the shield and the center of the cornucopia are high points. Yet, these areas are often weakly struck. On borderline coins, I mainly look to see if the luster is broken or not. On Dineros of the 1890's and later, the elbow is higher and may be a first point of wear. The breast is also higher, but is often weakly struck. On the reverse of the later Dineros, look at the bottom of the center leaf directly to the right of the cornucopia.

Planchet and Die Issues Seen on Dineros that may effect the grade:

- Die Lines: Thin lines will appear in the field due to polishing of the dies. They may be parallel, cross-hatch, circular, or a mix of these. These are commonly seen on the reverses of the later date Dineros, but can appear on any date. They sometimes rotate in the light and should not be confused with cleaning or damage. Generally no points are taken off for die lines.

- Die Scratches and Die Chatter: These occur when the die is cleaned with a brush or the dies become clogged with dirt. To the untrained eye these may appear to be contact/damage. The 1905 Dineros often have die scratches and chatter, as do do some of the early 1900's dates. Sometimes NGC will take off one or two points for these, sometimes not, depending on the size and severity.

- Adjustment Marks: These are parallel marks that will usually show at the rim. When the coin blank is too heavy, the mint will file it down to a proper weight, sometimes leaving marks. These are usually only seen on the Dineros of the mid-1890's, if at all. NGC may take a point off if they are strong.

Mint State Grading:

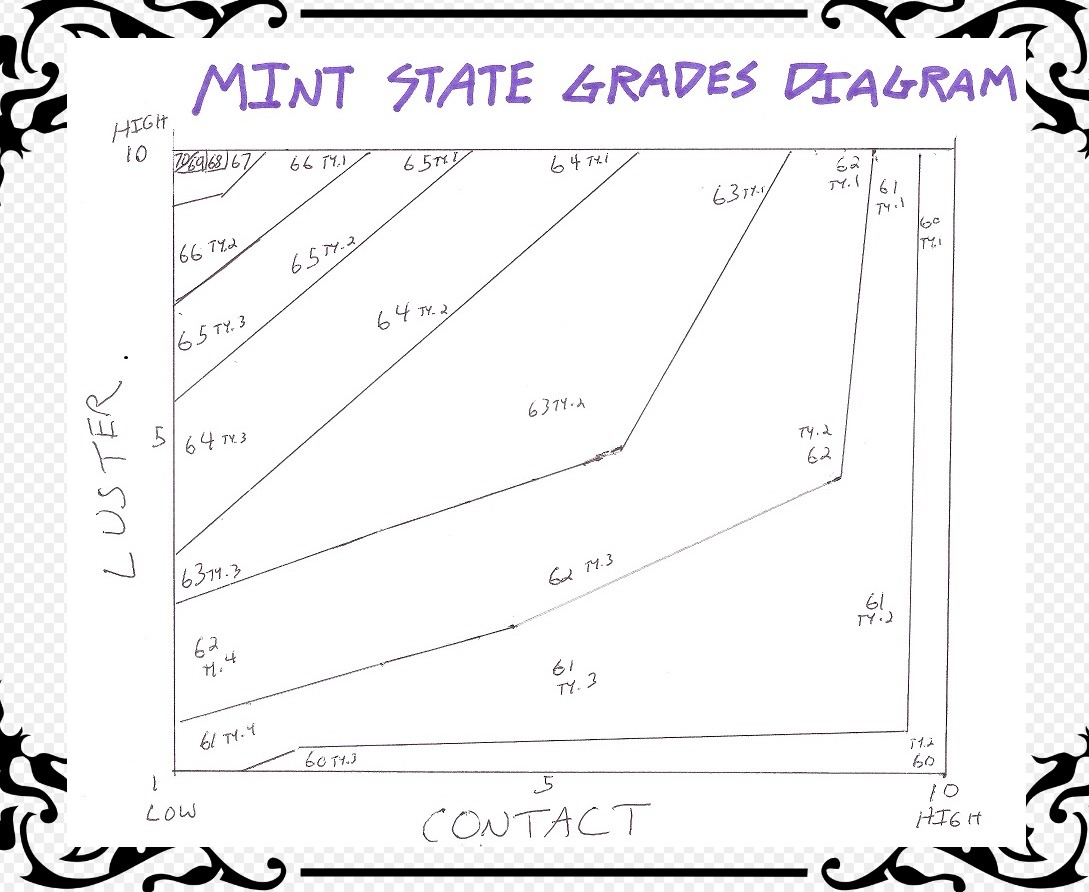

This is a diagram I came up with to show the range of possibilities within each grade, using luster and contact as the main determinants of grade. Poor strike or ugly toning may reduce the grade, and exceptional toning may increase it, but generally quality of luster and amount of contact are the main factors.

Note: If a Dinero has an MS 65 reverse (date side) but MS 63 obverse, it will be held to the MS 63 level. NGC generally does not take off points for fingerprints.

Grade Discussion:

MS 68: Same as MS 67 but only a couple very small inconsequential ticks in non-prime focal areas. Must have great eye-appeal.

MS 67: Luster must be full, strong and original. No major contact. Some very minor contact in the fields is allowed. Die lines may be present, and some small amount of die chatter is allowed. Toning, if present, must be at worst neutral, and luster must be full under the toning.

MS 66:

Type 1: Same as the MS 67 above with full luster, but with a bit more scattered contact. This contact should only be in small patches and not distracting.

Type 2: A coin with very good, but not full blazing luster. This coin should have essentially no marks at all in the field to make up for the lack of superb luster.

Note: In my experience, NGC has sometimes been harsh on coins with no or trivial contact and basically full luster. If the luster is not "blazing" they will sometimes still give a "66". Some of these coins are essentially as struck.

MS 65:

All MS 65 coins must have at least good luster. At this level, they are on a continuum from blazing luster with light scattered contact, to good but subdued luster and no contact.

Type 1: Almost the same intense luster as an MS 67, but has light contact scattered around the fields. This contact must be scattered mostly evenly in the fields with no strong hits. Some Dineros are basically as struck, but have a lot of die chatter, which can hold them back to the Gem level sometimes.

Type 2: Mid-way between types 1 and 3. Very good, MS 66 type luster, but enough scattered contact to hold it back one point. Heavy/dark toning can sometimes hold this type back from being a 66.

Type 3: Like the MS 66 type 2, this coins has trivial or no contact, but not quite enough freshness or "pop" with the luster to get to a 66. Luster still must be quite good overall.

MS 64:

Type 1: With strong Gem-y luster and moderate scattered contact, but nothing major. The amount of contact is what holds this coin back from being a 65 or better.

Type 2: Inbetween Types 1 and 3, good but not great luster with evenly scattered contact.

Type 3: With average luster and extremely clean fields. The luster is what holds this coin back from a higher grade.

MS 63:

Type 1: High end Gem quality luster but with moderate contact in most of the fields. Can be a couple of heavy hit areas. Too much contact for MS 64 Type 1.

Type 2: Mid-way between Types 1 and 3. Luster will be good, but not Gem quality, and there will be moderate scattered contact.

Type 3: Essentially no contact, but the luster is below average or may be a bit impaired. Still must be of at least average to above average eye appeal.

MS 62:

Type 1: Gem quality luster, but with a lot of contact, some heavy. Not often seen with Dineros.

Type 2: Average luster with moderately heavy contact.

Type 3: Fair to average and/or impaired luster with moderate contact.

Type 4: Fair and/or impaired luster with minimal to lighter contact. May be unattractively toned or have light hairlines. Sometimes may be attractive with just not enough luster to get to the 63 level.

MS 61: The lowest grade generally possibly for Dineros in mint state. While many MS 61 coins are unattractive, sometimes they are of average eye-appeal.

Type 1: Strong luster with heavy contact all over. This is very unlikely to be seen on Dineros.

Type 2: Average luster with heavy contact and hairlines in prime focal areas. May show signs of light cleaning/handling. May be light scratches. Low to average eye appeal.

Type 3: Poor to fair and/or impaired luster with moderate to medium-heavy contact. May have unattractive toning. May show signs of light cleaning/handling. May have light scratches.

Type 4: Limited contact, but not good enough luster to make it to the 63 level.

MS 60: This grade is no longer used for smaller coins like Dineros. It is generally reserved for larger coins with considerable bag marks across the entire coin. This grade spans a continuum from very high contact with good luster (Type 1) to very high contact with poor luster (Type 2) to lower contact with poor luster (Type 3). Strike may be poor. Light cleaning/handling likely. No wear, however.

A Word About Pricing:

You may notice that my set, while offering some comments on the Standard Catalog (Krause) price points for some coins, has a paucity of pricing data overall for Dineros. This is simply because many dates rarely trade hands in grades above average circulated.

For the most common later dates in NGC holders, general pricing is as follows: MS 63: $20-$30, MS 64: $25-$40, MS 65: $35-$60, MS 66: $50-$75, MS 67: $70-$120. Of course, there are no hard and fast rules here, and these prices vary depending on the eye-appeal of any given coin offered and the venue where it is sold. Raw common mint state Dineros will often sell online for half-off the slabbed pricing, which is true of all decimal Peru series. Part of the reason for this is the risk of buying a coin based on often low-quality photographs.

Further Reading:

My registry set is a one-stop location for all information about the Peruvian Dinero series. It synthesizes knowledge from the sources below and adds my own extensive research. That said, any Peruvian numismatist should add many of the following sources to their library, especially for information on other Peruvian series.

History:

Flatt, Hoarce P. 2000. The Coins of Independent Peru. Volume VI: Decimal Silver coins, 1858-1935. Terrell, Texas. Haja Enterprises.

This is the first book to buy on the Decimal Peru series. Flatt gives historical background with an Appendix discussing varieties. Out of print and now hard to find. Flatt's research is impressive, but he is focusing more on the historical/economic/political background of Peruvian numismatics than on the study of individual dates, as my set does.

Flatt, Hoarce P. 1994. The Coins of Independent Peru. Volume II: 1858-1917. Terrell, Texas. Haja Enterprises.

Similar to the work above, but focused on the history of all decimal coins, including fiduciary and gold. A must have. Copies are easier to find than for Volume VI. For more information on the Dinero antecedants, see Volume I.

Pricing:

Almanzar, Al and Seppa, Dale A. 1972. The Coins of Peru 1822-1972. San Antonio. Almanzar's Coins of the World.

Prices are very out of date. Yet, Almanzar/Seppa priced some dates more accurately than Krause. Cheap copies available.

The Standard Catalog/Krause prices are now free on the NGC World Price Guide: https://www.ngccoin.com/price-guide/world/

Excellent online resource. Thanks NGC!

On Patterns:

Christensen, William B. "Pattern Coinage of Peru." Article in "The Coinage of El Peru" by William L. Bischoff. American Numismatic Society. pp 177-190.

Important article for understanding Peru's patterns.

Flatt, Horace P., "The Flawed Peruvian Proof Coins of 1886." American Journal of Numismatics (1989-) Vol. 2 (1990), pp. 151-165.

Flatt, Hoarce P. 1986. "The First Foreign Coins Struck at the Philadelphia Mint." The Numismatist 99:38-43.

Very good article with primary sources.

On the Cuzco and Areiquipa Dineros:

Yabar Acuna, Francisco. 1996. Las últimas acuñaciones provinciales, 1883-1886 : las casas de moneda de Cuzco y Arequipa después de la Guerra del Pacífico. Lima. Editora Impresor Amarilys eirl.

Spanish only. Almost never available in the United States. English readers can use the Google translate app on their phone or tablet to translate text. You can photograph one page at a time and read the text on your device. Also see Flatt Volume V for Cuzco discussion. See Yabar's book "Monedas Fiduciarias Del Peru 1822 - 2000" for discussion of the 1879 and 1880 10 Centavos.

Set Goals

This is a diagram I came up with to show the range of possibilities within each grade, using luster and contact as the main determinants of grade. Poor strike or ugly toning may reduce the grade, and exceptional toning may increase it, but generally quality of luster and amount of contact are the main factors.

Note: If a Dinero has an MS 65 reverse (date side) but MS 63 obverse, it will be held to the MS 63 level. NGC generally does not take off points for fingerprints.

Grade Discussion:

MS 68: Same as MS 67 but only a couple very small inconsequential ticks in non-prime focal areas. Must have great eye-appeal.

MS 67: Luster must be full, strong and original. No major contact. Some very minor contact in the fields is allowed. Die lines may be present, and some small amount of die chatter is allowed. Toning, if present, must be at worst neutral, and luster must be full under the toning.

MS 66:

Type 1: Same as the MS 67 above with full luster, but with a bit more scattered contact. This contact should only be in small patches and not distracting.

Type 2: A coin with very good, but not full blazing luster. This coin should have essentially no marks at all in the field to make up for the lack of superb luster.

Note: In my experience, NGC has sometimes been harsh on coins with no or trivial contact and basically full luster. If the luster is not "blazing" they will sometimes still give a "66". Some of these coins are essentially as struck.

MS 65:

All MS 65 coins must have at least good luster. At this level, they are on a continuum from blazing luster with light scattered contact, to good but subdued luster and no contact.

Type 1: Almost the same intense luster as an MS 67, but has light contact scattered around the fields. This contact must be scattered mostly evenly in the fields with no strong hits. Some Dineros are basically as struck, but have a lot of die chatter, which can hold them back to the Gem level sometimes.

Type 2: Mid-way between types 1 and 3. Very good, MS 66 type luster, but enough scattered contact to hold it back one point. Heavy/dark toning can sometimes hold this type back from being a 66.

Type 3: Like the MS 66 type 2, this coins has trivial or no contact, but not quite enough freshness or "pop" with the luster to get to a 66. Luster still must be quite good overall.

MS 64:

Type 1: With strong Gem-y luster and moderate scattered contact, but nothing major. The amount of contact is what holds this coin back from being a 65 or better.

Type 2: Inbetween Types 1 and 3, good but not great luster with evenly scattered contact.

Type 3: With average luster and extremely clean fields. The luster is what holds this coin back from a higher grade.

MS 63:

Type 1: High end Gem quality luster but with moderate contact in most of the fields. Can be a couple of heavy hit areas. Too much contact for MS 64 Type 1.

Type 2: Mid-way between Types 1 and 3. Luster will be good, but not Gem quality, and there will be moderate scattered contact.

Type 3: Essentially no contact, but the luster is below average or may be a bit impaired. Still must be of at least average to above average eye appeal.

MS 62:

Type 1: Gem quality luster, but with a lot of contact, some heavy. Not often seen with Dineros.

Type 2: Average luster with moderately heavy contact.

Type 3: Fair to average and/or impaired luster with moderate contact.

Type 4: Fair and/or impaired luster with minimal to lighter contact. May be unattractively toned or have light hairlines. Sometimes may be attractive with just not enough luster to get to the 63 level.

MS 61: The lowest grade generally possibly for Dineros in mint state. While many MS 61 coins are unattractive, sometimes they are of average eye-appeal.

Type 1: Strong luster with heavy contact all over. This is very unlikely to be seen on Dineros.

Type 2: Average luster with heavy contact and hairlines in prime focal areas. May show signs of light cleaning/handling. May be light scratches. Low to average eye appeal.

Type 3: Poor to fair and/or impaired luster with moderate to medium-heavy contact. May have unattractive toning. May show signs of light cleaning/handling. May have light scratches.

Type 4: Limited contact, but not good enough luster to make it to the 63 level.

MS 60: This grade is no longer used for smaller coins like Dineros. It is generally reserved for larger coins with considerable bag marks across the entire coin. This grade spans a continuum from very high contact with good luster (Type 1) to very high contact with poor luster (Type 2) to lower contact with poor luster (Type 3). Strike may be poor. Light cleaning/handling likely. No wear, however.

A Word About Pricing:

You may notice that my set, while offering some comments on the Standard Catalog (Krause) price points for some coins, has a paucity of pricing data overall for Dineros. This is simply because many dates rarely trade hands in grades above average circulated.

For the most common later dates in NGC holders, general pricing is as follows: MS 63: $20-$30, MS 64: $25-$40, MS 65: $35-$60, MS 66: $50-$75, MS 67: $70-$120. Of course, there are no hard and fast rules here, and these prices vary depending on the eye-appeal of any given coin offered and the venue where it is sold. Raw common mint state Dineros will often sell online for half-off the slabbed pricing, which is true of all decimal Peru series. Part of the reason for this is the risk of buying a coin based on often low-quality photographs.

Further Reading:

My registry set is a one-stop location for all information about the Peruvian Dinero series. It synthesizes knowledge from the sources below and adds my own extensive research. That said, any Peruvian numismatist should add many of the following sources to their library, especially for information on other Peruvian series.

History:

Flatt, Hoarce P. 2000. The Coins of Independent Peru. Volume VI: Decimal Silver coins, 1858-1935. Terrell, Texas. Haja Enterprises.

This is the first book to buy on the Decimal Peru series. Flatt gives historical background with an Appendix discussing varieties. Out of print and now hard to find. Flatt's research is impressive, but he is focusing more on the historical/economic/political background of Peruvian numismatics than on the study of individual dates, as my set does.

Flatt, Hoarce P. 1994. The Coins of Independent Peru. Volume II: 1858-1917. Terrell, Texas. Haja Enterprises.

Similar to the work above, but focused on the history of all decimal coins, including fiduciary and gold. A must have. Copies are easier to find than for Volume VI. For more information on the Dinero antecedants, see Volume I.

Pricing:

Almanzar, Al and Seppa, Dale A. 1972. The Coins of Peru 1822-1972. San Antonio. Almanzar's Coins of the World.

Prices are very out of date. Yet, Almanzar/Seppa priced some dates more accurately than Krause. Cheap copies available.

The Standard Catalog/Krause prices are now free on the NGC World Price Guide: https://www.ngccoin.com/price-guide/world/

Excellent online resource. Thanks NGC!

On Patterns:

Christensen, William B. "Pattern Coinage of Peru." Article in "The Coinage of El Peru" by William L. Bischoff. American Numismatic Society. pp 177-190.

Important article for understanding Peru's patterns.

Flatt, Horace P., "The Flawed Peruvian Proof Coins of 1886." American Journal of Numismatics (1989-) Vol. 2 (1990), pp. 151-165.

Flatt, Hoarce P. 1986. "The First Foreign Coins Struck at the Philadelphia Mint." The Numismatist 99:38-43.

Very good article with primary sources.

On the Cuzco and Areiquipa Dineros:

Yabar Acuna, Francisco. 1996. Las últimas acuñaciones provinciales, 1883-1886 : las casas de moneda de Cuzco y Arequipa después de la Guerra del Pacífico. Lima. Editora Impresor Amarilys eirl.

Spanish only. Almost never available in the United States. English readers can use the Google translate app on their phone or tablet to translate text. You can photograph one page at a time and read the text on your device. Also see Flatt Volume V for Cuzco discussion. See Yabar's book "Monedas Fiduciarias Del Peru 1822 - 2000" for discussion of the 1879 and 1880 10 Centavos.